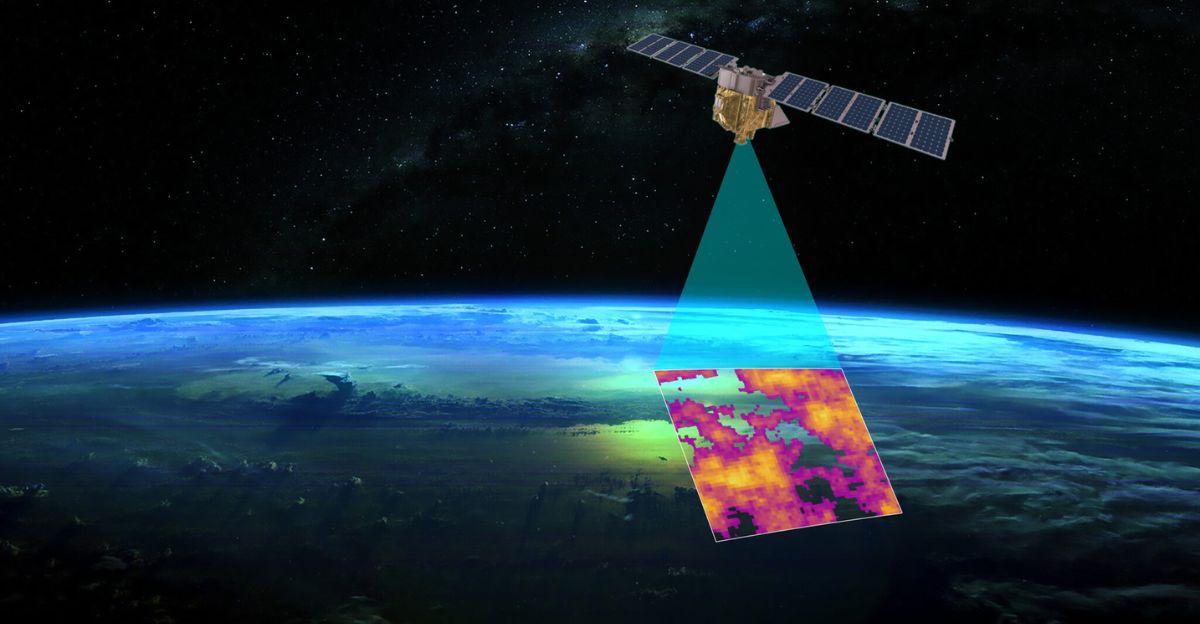

California’s Tanager-1 satellite has achieved what federal agencies long avoided: exposing methane leaks that were invisible to the public. Since May 2025, it has identified and helped eliminate 10 major leaks, preventing emissions equal to removing 18,000 cars from the road each year.

Passing over the state 4–5 times weekly, it marks the first state-led orbital methane monitoring program. As federal climate tools are dismantled, California proves states can fill the void—and raises the question of who’ll act before national monitoring disappears entirely.

Methane: The 80× Multiplier

Methane heats the planet up to 80 times faster than carbon dioxide over two decades, making it a critical near-term climate threat. Because it dissipates within about ten years, cutting methane offers fast climate benefits.

California’s quarterly inspection rules reveal gaps that satellites now expose in real time. The 10 leaks stopped so far avoided roughly 18,000 metric tons of CO₂-equivalent annually. Compared to expensive manual inspections, orbital monitoring transforms methane oversight from occasional snapshots to continuous enforcement.

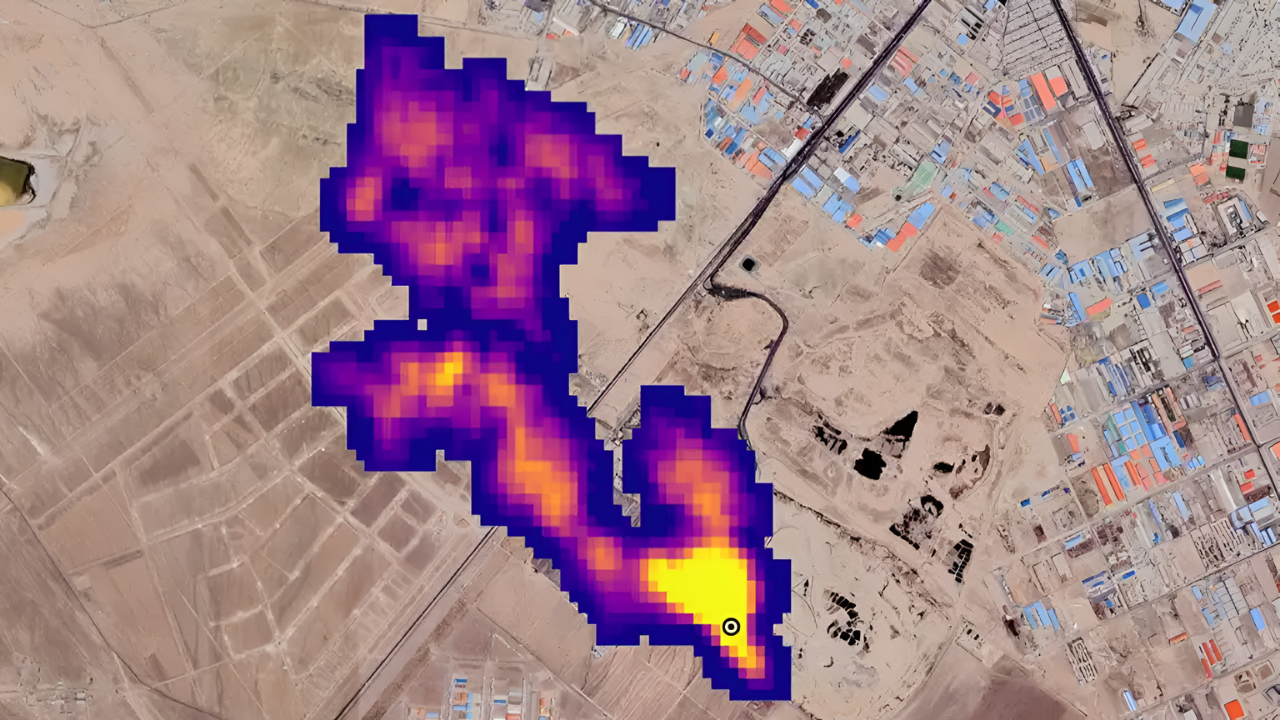

The 24-Hour Proof of Concept

In July 2025, Tanager-1 spotted a massive methane plume over a Kern County oil field. Regulators notified the operator immediately, and the leak was repaired within 24 hours—verified again by satellite. This speed overturns old enforcement models where detection to repair could take months.

Instead of waiting for quarterly inspections, operators now face same-day exposure. The financial incentives are clear: less wasted gas, faster compliance verification, and immediate climate benefits. One orbital pass proved enforcement can move at space-age speed.

The Partnership That Built Tanager-1

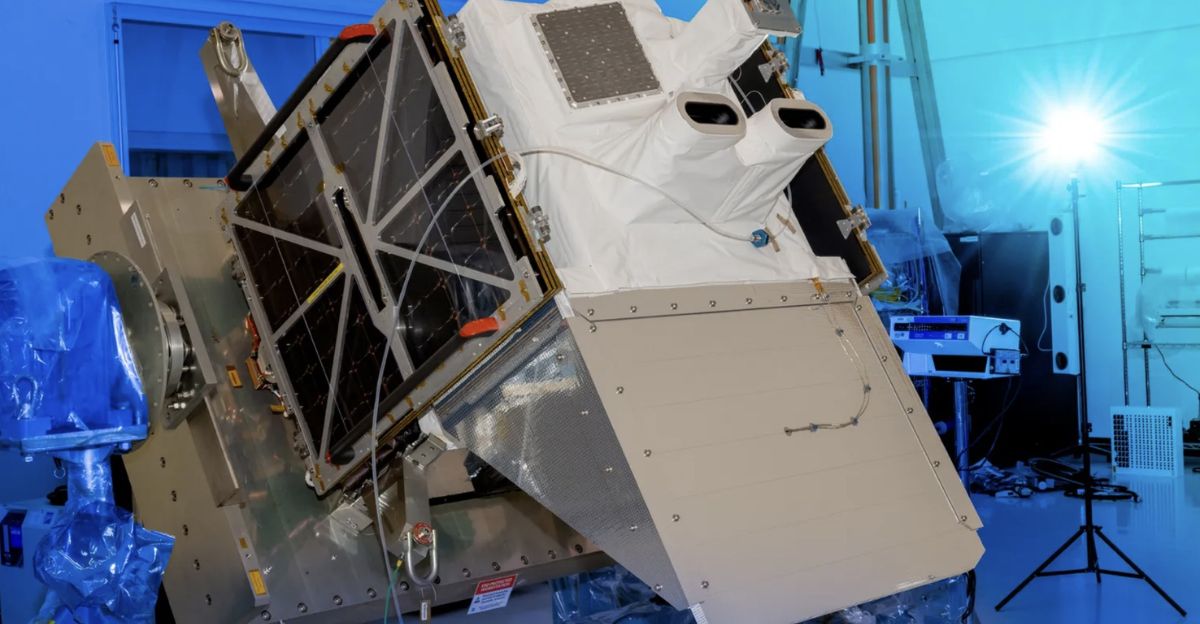

Tanager-1 was created by a coalition led by Carbon Mapper, linking NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Planet Labs, and the California Air Resources Board. Planet Labs built the satellite, JPL developed the hyperspectral instrument, and Carbon Mapper processes the emissions data.

California committed $100 million for satellite data through 2030—the first long-term state investment in orbital climate monitoring. Three more Tanager satellites arriving in 2026–2027 will expand global coverage, showing how philanthropic, commercial, state, and federal research institutions can collaborate effectively.

Federal Sabotage: Climate Satellite Shutdowns

NASA has been ordered to deactivate the operational OCO-2 and OCO-3 carbon-monitoring missions, despite both functioning perfectly. OCO-2 could run until 2040 but is being deliberately deorbited, destroying a $467 million asset. OCO-3 will also be shut down despite providing critical data on photosynthesis, drought, and crop health.

NASA staff confirmed these decisions were pushed internally long before Congress approved budgets. This dismantling is unprecedented—an ideologically driven attack on climate science rather than a technical or financial necessity.

EPA’s Data Blackout Strategy

In September 2025, the EPA moved to eliminate the Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program, which has required about 8,000 facilities to report emissions since 2009. The proposal removes reporting for 46 industrial categories and suspends oil and gas reporting until 2034—creating a nine-year blackout during a crucial climate decade.

Although framed as a cost-saving measure, eliminating this data cripples policymaking, emissions trading systems, and public oversight. With no federal transparency, industry emissions become effectively unknowable.

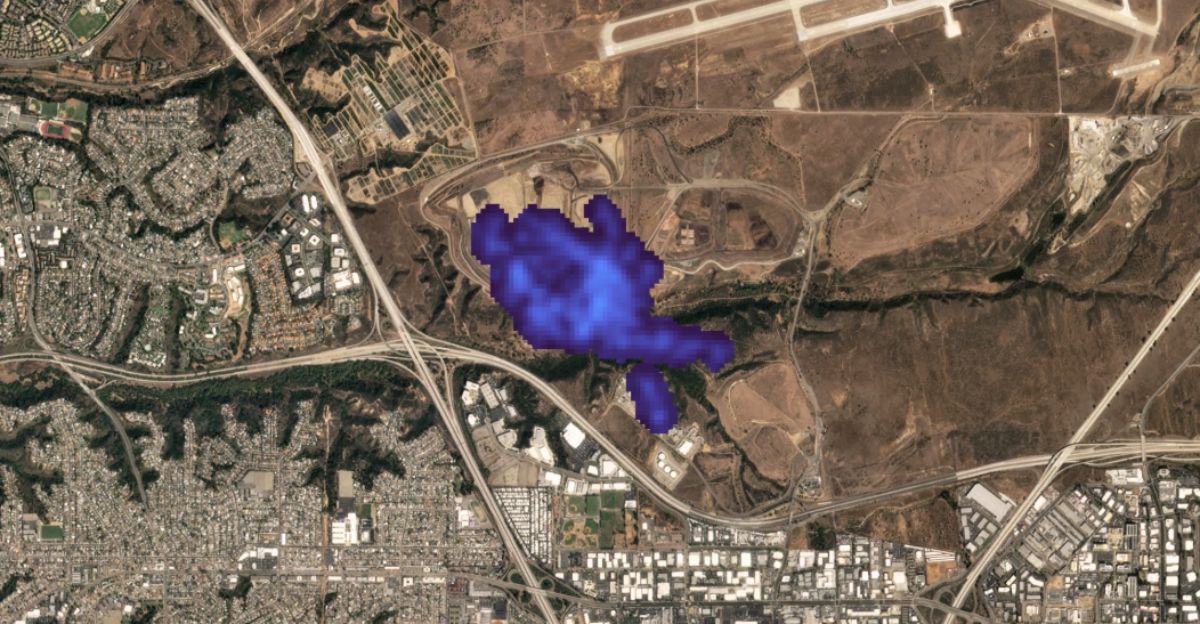

California’s $100 Million Bet

California committed $100 million to purchase Tanager data through 2030, treating satellite monitoring as critical climate infrastructure. Compared to billions in future climate damages, the investment is modest. Aircraft-based surveys are costly and limited, while Tanager-1 scans roughly 50,000 square miles daily.

CARB’s public dashboard adds transparency, pressuring operators to act quickly. As federal climate monitoring collapses, California demonstrates that states can independently fund the scientific tools necessary to enforce emissions rules and inform policy.

The Detection Technology Breakthrough

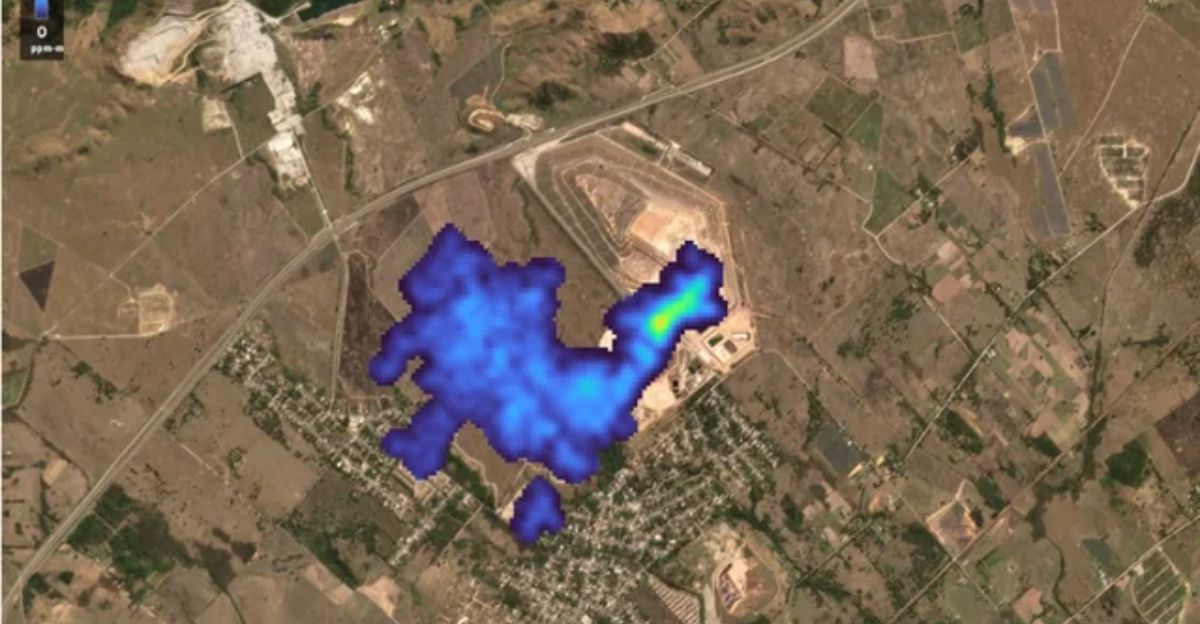

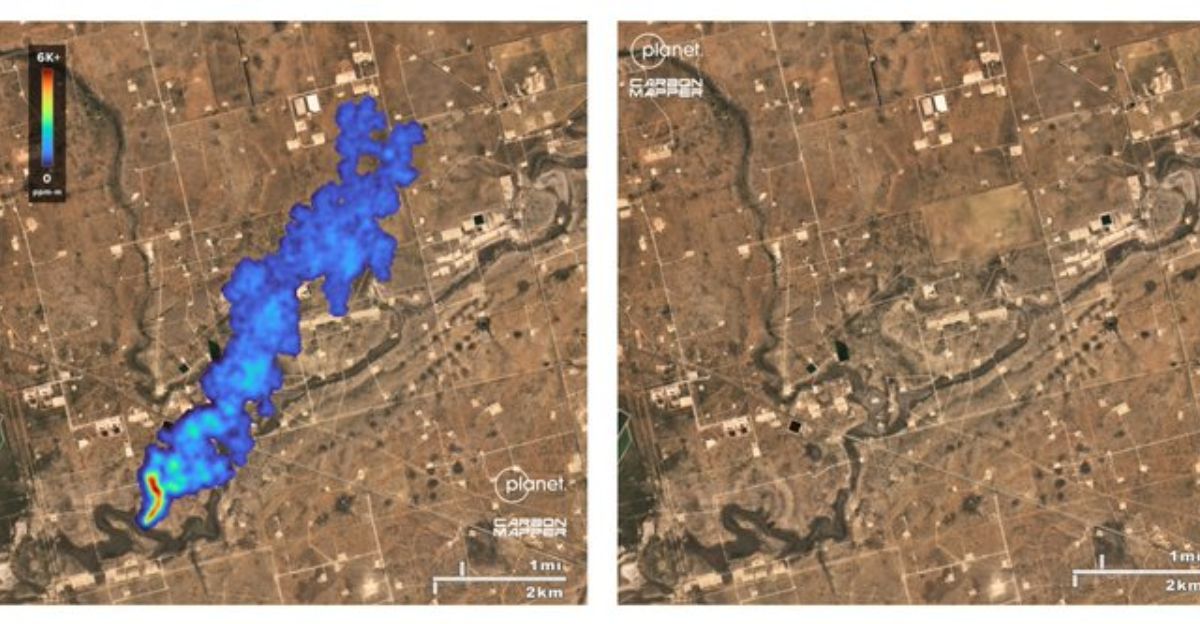

Tanager-1 uses a hyperspectral spectrometer that analyzes hundreds of wavelengths in visible and infrared light, identifying methane and CO₂ through their absorption signatures. Unlike older satellites that detected only regional methane hotspots, Tanager-1 pinpoints individual wells, pipelines, and compressors.

This precision removes ambiguity about leak sources and quantifies emission rates almost instantly. Carbon Mapper publishes this data publicly, shifting informational power from industry to regulators and communities and enabling unprecedented transparency in emissions monitoring.

Ten Leaks Stopped: What We Learned

Since May 2025, Tanager-1 has found 10 major methane leaks at California oil and gas sites—each repaired after notification. The avoided emissions equal roughly 82,800 metric tons of CO₂-equivalent per year.

With about 1.7 major leaks found per month, California could see 40–50 annually once the satellite completes a full year of operations. Each large leak represents $200,000–$500,000 in lost natural gas, meaning the program has already prevented $2–5 million in losses—proof that monitoring pays for itself.

What Still Goes Undetected

Although Tanager-1 passes over California every 1.5 days, leaks that start and stop between overpasses remain invisible. The satellite detects only large emissions, missing numerous smaller but cumulatively significant leaks. It also excludes federal lands, offshore platforms, and interstate pipelines.

Scaling California’s leak rate to the national oil and gas sector suggests hundreds of major leaks remain undetected across the U.S. And agricultural methane—another massive source—is outside Tanager-1’s monitoring scope entirely.

The Permian Basin Case Study

In October 2024, Tanager-1 spotted a major methane plume from a gathering pipeline in the Permian Basin. Carbon Mapper alerted Texas regulators and federal officials, and the operator voluntarily repaired the leak.

This case shows how California’s investment benefits the entire country: the satellite tracks whatever it flies over, regardless of jurisdiction. Even without strong state regulations, operators responded due to public data transparency. One satellite demonstrated that visibility alone can drive national methane reductions.

“A New Era” in Methane Tracking

CARB Deputy Executive Officer Lauren Sanchez described Tanager-1 as “the start of a new era” in methane monitoring during a COP30 announcement.

She captured the shift from infrequent operator-led inspections to continuous, regulator-driven orbital verification. Instead of relying on self-reported leaks, regulators now independently confirm emissions with hard data regardless of operator cooperation. Her statement also underscored a deeper reality: states must innovate because federal agencies are dismantling the very systems they once led.

Three More Satellites on the Way

Carbon Mapper will deploy three additional Tanager satellites in 2026–2027, creating a constellation capable of daily or twice-daily global coverage. This redundancy strengthens monitoring reliability and compresses detection-to-repair timelines even further.

Planet Labs’ extended contract ensures data processing and long-term operational stability through 2030. As federal climate monitoring disappears, this constellation becomes a de-facto replacement for national capacity—operated through a public-private-philanthropic coalition instead of a federal agency.

Why Washington Prefers Darkness

Destroying functional satellites and eliminating emissions reporting doesn’t save money—it destroys data. Without emissions data, policymakers can argue climate problems don’t exist or can’t be measured. Eliminating records between 2025 and 2034 ensures trend analysis becomes impossible, blocking accountability.

Shutting down satellites rather than transferring them to state or academic institutions shows the motive clearly: preventing climate monitoring takes priority over protecting taxpayer investments or national scientific capacity.

The Subnational Climate Sovereignty Shift

California’s satellite initiative signals a new era where states build their own climate monitoring systems independent of the federal government. States or interstate coalitions could create multi-satellite constellations with global reach, bypassing national political obstruction.

With declining launch costs and maturing commercial satellite technology, the question becomes not whether states can afford this—but whether they can afford not to. This shift could redefine environmental governance by decentralizing climate surveillance power.

The Quarterly Inspection Gap

California’s quarterly methane inspection rules leave 90-day windows when leaks can persist undetected. Even when leaks are found, operators often have 15–30 days to complete repairs. Inspections depend on operator cooperation, equipment quality, weather, and human accuracy. Satellite monitoring eliminates these weaknesses.

Tanager-1’s early findings suggest several major leaks emerged between ground inspections or were missed entirely—proving that regulatory rules alone cannot ensure compliance without independent verification from space.

Fixing the Atmospheric Accounting Problem

Methane’s short atmospheric lifetime makes rapid reductions vital for near-term climate stability—but only if emissions are measured accurately. Eliminating federal reporting programs erases the baselines needed to prove whether emissions fall or rise.

California’s satellite system restores this accounting capacity by supplying independent, verifiable measurements. This matters for carbon markets, corporate net-zero claims, and international climate commitments. Without reliable data, climate policy becomes guesswork; with satellite monitoring, it becomes scientifically grounded.

Economics Versus Regulation

Methane leaks aren’t just environmental failures—they’re financial losses. The 10 leaks repaired because of Tanager-1 saved operators an estimated $2–5 million in lost product. Once operators see quantified emissions, fixing leaks becomes economically rational, even without new regulations.

The Kern County 24-hour repair exemplifies this dynamic: transparent detection made delay unprofitable. This suggests global methane reduction may hinge less on mandates and more on visibility that makes waste impossible to ignore.

Second- and Third-Order Effects

Satellite monitoring reshapes more than emissions enforcement. Insurers may require methane data before underwriting fossil fuel operations. Investors may tie financing to verified emissions performance. Trade partners could demand satellite-validated methane intensities for imported natural gas. Legal liability could expand when satellite archives show years of preventable leaks.

Communities may demand monitoring for environmental justice. And internationally, governments may partner directly with satellite operators, circumventing federal climate diplomacy entirely.

What Comes Next?

Tanager-1 proves that climate monitoring isn’t something only federal agencies can do—states, nonprofits, and commercial operators can build parallel systems.

With three more satellites launching by 2027 and federal monitoring programs being dismantled, a decentralized climate surveillance architecture is emerging. States that invest in monitoring will understand their emissions and act accordingly. Those that don’t will navigate climate hazards blindly. California has already chosen data over darkness. Now others must decide whether they will too.