In the autumn of 2024, a 76-year-old hiker stumbled upon something extraordinary: wooden posts jutting from Norwegian ice at 4,600 feet. The discovery was a 1,500-year-old reindeer hunting facility preserved in near-perfect condition. It is Europe’s only wooden trap of its kind, exposing Iron Age strategy and labor. Yet the same melt that revealed it also threatens it, creating a dilemma.

A Hiker’s Remarkable Mountain Discovery

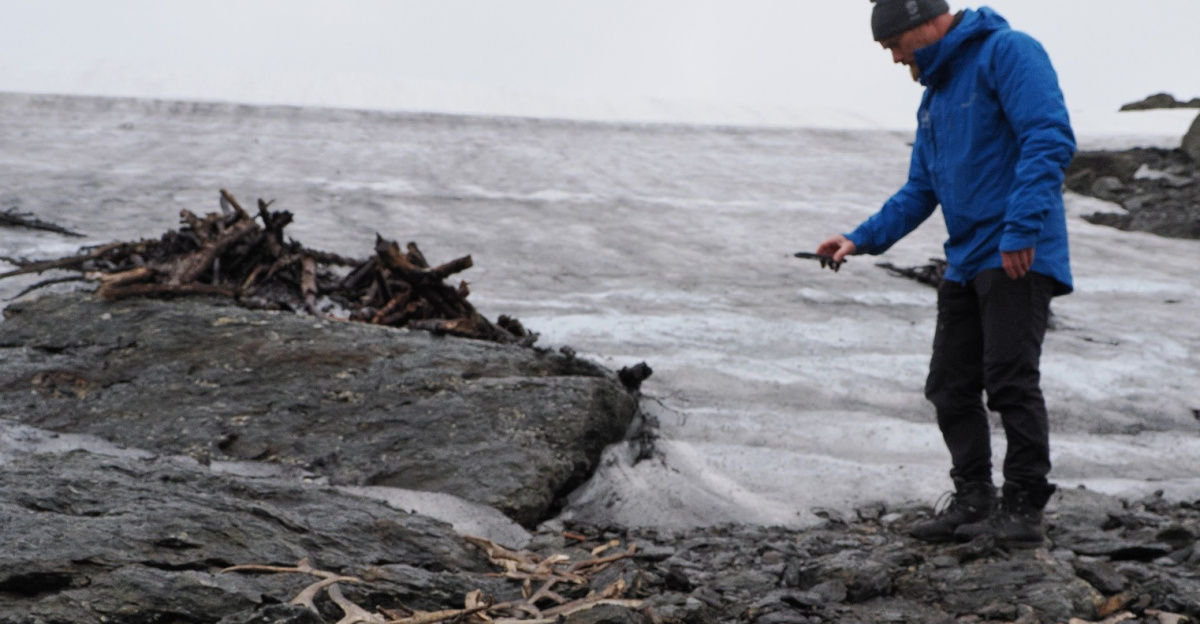

Helge Titland, a seasoned local mountaineer, descended the Aurlandsfjellet plateau last autumn and spotted wooden stakes protruding through melting snow. He reported it to archaeologists at the University Museum of Bergen, triggering a major investigation. Snow fell before researchers could reach the site, delaying excavation for 1 year. When teams returned last summer with equipment, the scene defied expectations.

“The First Time” Wood Survived

“This is the first time a mass-capture facility made of wood has emerged from the ice in Norway, and the facility is probably also unique in a European context,” said Øystein Skår, archaeologist at Vestland County Municipality, according to the museum’s November 2024 statement.

Stone systems were known, but wood rarely survives. Ice rewrote the rules, and questions lingered beneath it.

Engineering An Ancient Hunting Apparatus

The trap shows sophisticated coordination. Two parallel wooden fences stretched about 1,000 feet wide, forming a funnel that drove reindeer into a narrow pen. Hundreds of logs and branches were hauled uphill by hand, weighing several tons in total. Hunters likely stood at chokepoints to finish the drive. It was not a simple snare but industrial-scale harvesting, and the debris field confirmed it.

“All the Antlers Have Carving Marks”

“All the antlers have carving marks, which gives us deeper insight into the hunting activity itself,” Øystein Skår explained in the Vestland County Municipality statement from November 15, 2024.

Hundreds of antlers lay near the kill zone, with cut marks consistent with axes. Many came from younger reindeer and females, suggesting selective harvesting. Larger buck antlers may have been saved for tools and trade, raising bigger economic questions.

Weapons Left In The Ice

The site also yielded iron spearheads, wooden arrow and bow fragments, and carved wooden implements of unknown purpose. Iron weapons signaled wealth and technological investment in the early Iron Age, when metal was precious. Archaeologists found 3 complete bows, implying multiple hunters coordinated kills. Arrow shafts show careful wood selection and craft, pointing to planned, repeatable hunts. But preservation was the real shock.

“So Well-Preserved It Looks New”

“The level of preservation is unlike anything we normally encounter, which makes it remarkable. The objects displayed at NAM looked as if they were made yesterday,” said Erik Kjellmann, who led the November 15, 2024 Norwegian Archaeology Meeting in Tromsø, according to Science Norway.

Cold, dark, damp ice halted decay. Wood that would vanish in soil stayed intact for 1,500 years, which made one odd artifact even stranger.

The Mystery Of The Decorated Oar

One puzzling find was a decoratively carved wooden oar recovered 1,400 meters, 4,600 feet, below the trap site. Why would a boat oar be high in the mountains, far from waterways? Archaeologists suspect it helped assemble barriers, yet ornamentation suggests meaning beyond function. It proves beauty mattered even in harsh work zones. That single object hinted at culture hiding inside the hunt.

“Research Material For Generations”

“This discovery is truly exceptional. The real detailed research and study of these things is going to come decades and centuries in the future. This is research material for archaeologists for generations,” said Leif Inge Åstveit, project leader at the University Museum of Bergen, according to Science Norway on December 4, 2024.

Tree rings, isotopes, and DNA could map dates, migrations, and herd genetics. But the melting clock is already ticking, and history shows why.

A Cold Period Sealed The Site

Evidence suggests the trap was abandoned around 500 CE when a climate shift brought colder temperatures. Heavier snowfall and persistent ice buried the facility and protected it for centuries, freezing the worksite exactly as it was left. Hunters never returned for equipment, and the mountain locked everything away. Now modern warming reverses that ancient cold snap, turning preservation into exposure with consequences.

Iron Age Norway’s Hunting Sophistication

The facility dates to the Early Iron Age, 500 BCE to 500 CE, when Scandinavia was changing socially and technologically. Iron tools enabled more complex strategies than stone or bone, and the scale suggests reindeer hunting underpinned local economies. Pelts and antlers became valuable commodities feeding wider networks, exported by the Viking Age later. The trap looks like infrastructure for trade, not just dinner.

A Top Honor Came Quickly

On November 15, 2024, the Norwegian Archaeology Meeting in Tromsø voted the site “Find of the Year,” beating other 2024 discoveries. The honor reflected rarity: never before had such intact wooden hunting infrastructure emerged from Norwegian ice. Researchers saw potential to reshape understanding of Iron Age mountain societies and unlock funding for continued work. Celebration, though, carried pressure, because thawing does not wait for permits.

Climate Change’s Double-Edged Reality

Modern warming creates a paradox. Retreating ice exposes artifacts preserved for millennia, yet once exposed, they begin to decay fast. Ice patches worldwide are melting 30 times faster than during the 1980s, according to monitoring data. In Norway, more than 4,500 artifacts have emerged since systematic documentation began. Similar revelations are accelerating in the Alps, Rockies, and Andes, raising a grim question.

“We Have Never Found Anything Like This”

“We have never found anything like this before. It is a completely unique find,” said archaeologist Øystein Skår in a translated statement from Vestland County Municipality in November 2024.

Typical mountain digs produce stone and metal because organics rot. Here, ice preserved wood, bone, and delicate traces of planning, revealing coordinated group activity rarely documented for the Iron Age. Each post reflects labor, timing, and intent, and the conservation challenge starts immediately after discovery.

Preserving Discoveries Before Time Runs Out

Once artifacts hit air and light, deterioration accelerates. Teams placed finds in freezers at the University Museum of Bergen for controlled thawing and drying. Wood must be stabilized to avoid cracking; antlers can flake; iron spearheads risk corrosion. Conservation can take months or years, but delays can destroy evidence in days. The procedures are meticulous, yet they cannot answer every mystery alone.

Mysteries Still Locked In Ice

Key questions remain. Despite evidence of hundreds of reindeer processed, no skeletons or major bones were found, suggesting meat transport or later scavenging. The decorated oar’s purpose and origin remain unresolved. How did Iron Age communities coordinate labor for a 1,000-foot funnel at 4,600 feet elevation? Tree-ring dating, isotope work, and DNA may clarify timelines and migrations, if enough material survives exposure.

“Building This Has Been Challenging”

“Building this has been challenging. Thousands of logs, weighing several tons in total, were transported high into the mountains,” said archaeologist Leif Inge Åstveit to Fox News Digital in an analysis of the construction effort from the November 10, 2024 Vestland County announcement.

At 4,600 feet, hauling loads is exhausting even with modern gear. Iron Age hunters did it without today’s equipment, then aligned fences into a precise funnel. The engineering implies planning, leadership, and repeat use, connecting this site to a global pattern.

Glacial Archaeology Is Surging Worldwide

Over the last 30 years, melting ice patches have produced thousands of artifacts. Canadian glaciers revealed 500-year-old moccasins and 10,000-year-old hunting tools. Alpine sites keep yielding textiles and weapons from the Bronze Age onward. Yukon ice patches produced arrows with fletching and sinew, and Peru’s high-altitude finds include rare Inca objects. Glacial archaeology now has a peer-reviewed journal launched 2014, but will evidence outlast the melt?

A Record Of Climate And Culture

The trap tells 2 intertwined stories: Iron Age hunting culture and climate vulnerability. The cold that preserved it for 1,500 years has reversed within a human lifetime. What stability protected, disruption now threatens to erase. The emergence is a symbol of anthropogenic warming and an archive of human ingenuity under harsh conditions. Whether it becomes a lesson or just a curiosity depends on choices made now.

Racing Against Time To Save History

Researchers will keep surveying Aurlandsfjellet in summer, hoping to recover more before exposure destroys it. Tree-ring analysis can tighten chronologies, while material studies may trace trade networks and resource exchange. Exhibitions could bring this hunting culture to wider audiences, but loss remains the dominant risk as ice vanishes. The trap endured 1,500 years by accident, and its future will not be accidental, will it?

Sources

Wooden Reindeer Trap Found in Norway’s Melting Ice. Archaeology Magazine, November 17, 2025

Norwegian archaeology find of the year: ‘So well-preserved that they appear to have been made yesterday’. Science Norway, December 4, 2024

Climate indicators. Norwegian Polar Institute, accessed January 2026

Global glacier change in the 21st century: Every increase in warming matters. Science Magazine, 2024