In November 2025, scientists at Queen Mary University of London and University College London revealed evidence of a sensory power once thought impossible: humans can detect objects before touching them. In controlled experiments, twelve adults sweept their fingers slowly through dry sand, searching for a hidden five-centimeter plastic cube.

Across 216 trials, participants detected the object remotely 79 times—at an average of 2.7 centimeters before contact, with over 70 percent accuracy. Signal detection analysis produced a robust d′ of 1.1973, confirming genuine perception rather than guesswork. Theoretical modeling places the maximum distance at 6.9 centimeters, revealing humans operate at roughly 39 percent of the physics-defined limit. As researcher Elisabetta Versace emphasized, this discovery “changes our conception of the perceptual world.”

Correcting a 2,400-Year-Old Mistake by Aristotle

Western culture has long accepted Aristotle’s ancient claim that humans have just five senses—sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch. This framework persists in education despite modern neuroscience identifying numerous additional sensory systems, such as proprioception and balance.

Aristotle argued no other senses existed because shared perceptual qualities like shape were handled by a “common sense,” not by new modalities. Remote touch overturns this foundational assumption: it shows humans detect objects through sand and other granular materials without physical contact, violating the premise that touch requires direct skin stimulation. As philosopher Barry Smith notes, contemporary neuroscience demands a multisensory model far beyond the constraints of Aristotle’s reasoning.

How Buried Objects Reveal Themselves Through Sand

Remote touch relies on the physics of granular media. As a finger moves through sand, it generates tiny mechanical disturbances. These disturbances travel through surrounding grains until they strike a buried object, which reflects altered wave patterns back toward the finger.

Human mechanoreceptors—Merkel discs, Ruffini endings, Meissner and Pacinian corpuscles—are sensitive enough to decode these reflected signals. Physics models predicted detection distances up to seven centimeters, exactly matching the study’s observed maximum of 6.9 centimeters. Human sensitivity aligned almost perfectly with these theoretical thresholds, revealing a perceptual ability never previously documented in primates.

Robots Sense Farther—But Humans Decide Better

To compare biological and artificial sensing, researchers built a robotic tactile probe on a UR5 arm and trained Long Short-Term Memory neural networks to interpret sand-generated signals. In 120 trials, the best LSTM model achieved perfect detection with 90 percent false-alarm avoidance and 91 percent precision.

Robots occasionally sensed objects nearly 13 centimeters away—farther than humans—but they produced far more false positives overall. Humans, by contrast, displayed superior judgment, perhaps integrating subtle proprioceptive cues machines cannot yet interpret. As researcher Lorenzo Jamone noted, human and robotic data enriched each other’s interpretation.

Shorebirds Mastered This Sense Long Before Humans

Though new to humans, remote touch is well-documented in shorebirds like sandpipers. These birds use specialized Herbst corpuscles in their beaks to sense mechanical reflections when probing sand for prey. Versace’s team intentionally modeled human experiments on bird foraging behavior—except humans lack any special anatomical adaptations.

Yet participants still performed comparably, thanks to the extraordinary density of mechanoreceptors in human fingertips. This suggests remote touch may emerge naturally whenever a species possesses receptors sensitive enough to interpret particle-transmitted mechanical waves.

Why This Sensory Ability Hid Until 2025

Remote touch escaped discovery because classical research treated touch solely as a contact-based sense. Traditional psychophysics used stationary subjects and direct skin stimulation, precluding detection of signals generated through active movement in loose media. Neuroscience also mapped mechanoreceptor fields only on the skin surface, ignoring the possibility that receptive boundaries extend into material surrounding the body.

Combined with the widespread assumption that all human senses were already catalogued, no one investigated “impossible” abilities. Remote touch now becomes the first entirely new human sensory modality identified in the twenty-first century.

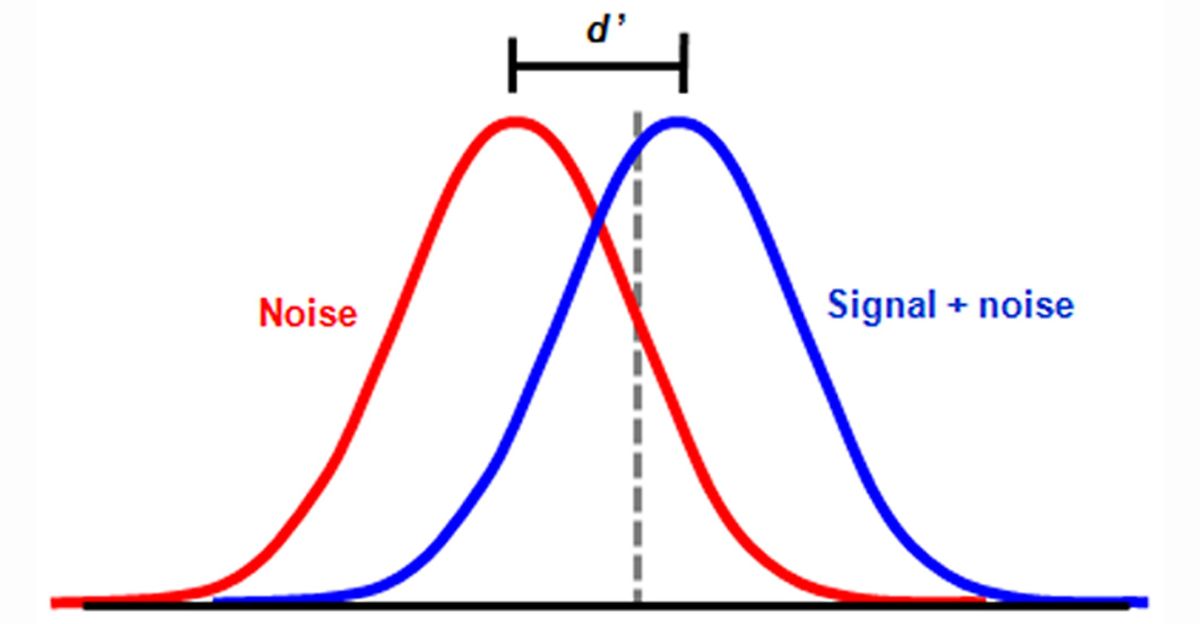

Proof Through Signal Detection Theory

To verify perception rather than chance, researchers applied signal detection theory, which quantifies true sensitivity by separating signal and noise distributions. The study achieved a d′ of 1.1973—well above the zero value indicating random guessing.

The response bias value of –0.112 revealed only a slight tendency toward reporting object presence, not enough to explain results via strategy alone. For comparison, experienced radiologists interpreting mammograms often achieve d′ values between 1.5 and 2.5. For a previously unknown human sense without training, 1.1973 represents remarkably strong perceptual performance.

A Robotics Market Set for a $1.8 Billion Surg

The tactile sensor market, valued at $500 million in 2025, is projected to approach $1.8 billion by 2033. Current systems rely on capacitive or piezoresistive sensors that require direct contact, limiting performance in visually obscured environments. Remote touch introduces an entirely new class of non-contact tactile sensing capable of detecting buried or occluded objects.

Potential uses range from archaeological surveying to planetary exploration. The study’s demonstration of LSTM-based detection with 91 percent precision provides a direct path to rapid commercialization in robotic manipulation and search systems.

Search-and-Rescue Robots Gain Crucial Pre-Contact Awareness

Collapsed structures trap roughly 125 million people annually worldwide. Search teams rely on dogs, thermal cameras, acoustic detectors, and radar tools—each with significant limitations.

Remote touch could give tactile robots the ability to detect voids, survivors, and unstable debris several centimeters before impact. A robot that receives warning 2.7 to nearly 13 centimeters ahead can slow or adjust course, avoiding dangerous collisions that destabilize rubble. Adding remote touch to existing snake-like rescue robots could dramatically increase survival odds without drastically raising costs.

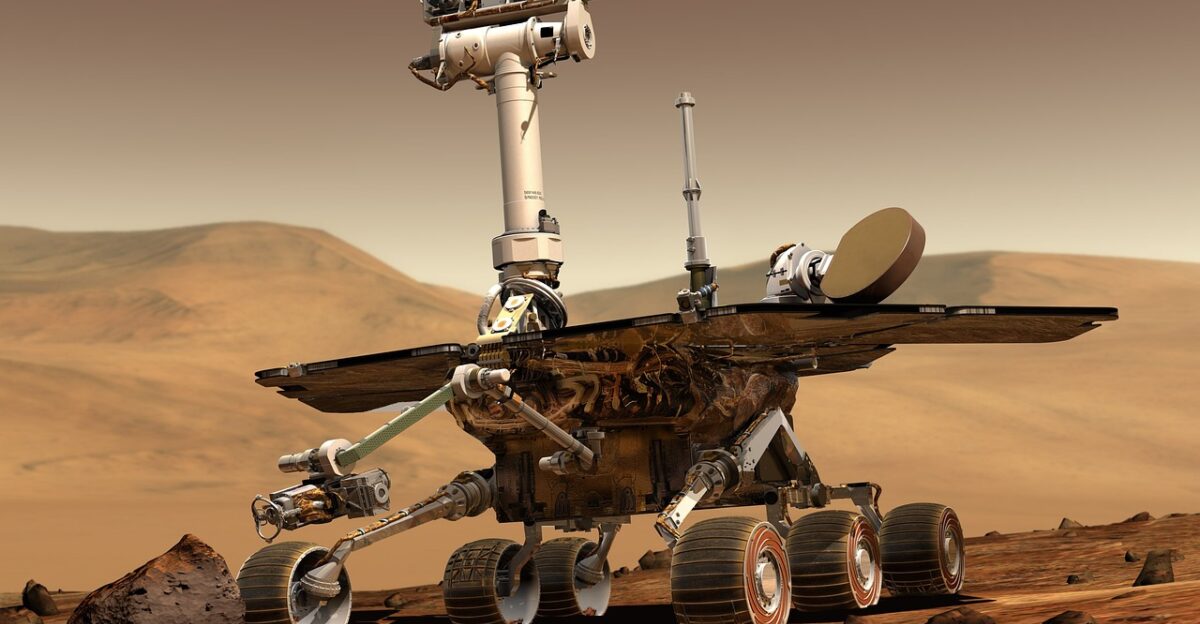

Why Mars Rovers Need “Fingertips,” Not Just Cameras

Martian rovers depend heavily on cameras and spectrometers, yet dust, low light, and obscured terrain often block visual information. Past missions have even become trapped in soft regolith, as with the Spirit rover in 2009.

Remote touch would allow rovers to detect buried rocks, ice layers, or soft patches before wheels make contact—effectively extending their sensory reach by up to 6.9 centimeters. Such tactile foresight could guide nighttime operations and prevent immobilizing accidents on unpredictable extraterrestrial landscapes.

Archaeology Without Destroying Priceless Artifacts

Despite adopting advanced mapping tools like LiDAR and ground-penetrating radar, archaeologists still damage countless small artifacts during excavation. Many objects—pottery, stone tools, bone fragments—leave no electromagnetic signature detectable by current survey methods.

Remote touch provides a mechanical alternative: tools equipped with tactile sensors could identify buried items a few centimeters before direct contact. With over half a million active dig sites globally, even a tiny reduction in excavation damage would preserve millions of artifacts that might otherwise be fractured or lost.

The Evolutionary Puzzle With No Clear Answer

Why would humans evolve the ability to sense objects through sand? No obvious ancestral behavior seems to demand it. One hypothesis links remote touch to extractive foraging—early hominins digging for roots, insects, or water sources might have benefited from detecting items before striking them.

Another possibility is exaptation, where mechanoreceptors evolved for fine tactile control incidentally gain the ability to detect granular reflections. Because humans already sense skin movements as small as ten nanometers, remote touch may require no specific adaptation to exist.

Global Textbooks Must Be Rewritten for 50 Million Students

Biology and psychology courses worldwide still teach the five-sense model, reinforcing outdated boundaries that define touch strictly as contact-based. This new discovery directly contradicts standard definitions still appearing in major academic references.

Updating curricula requires multi-year revisions across global education systems serving roughly 50 million students annually. Remote touch challenges how textbooks organize sense systems and demands a shift toward describing perception as integrated, dynamic, and environmentally extended. Its inclusion will fundamentally reshape modern sensory science education.

Biohackers See a New Frontier of Human Enhancement

For the biohacking community, remote touch confirms that human sensory limits remain far from fully mapped. If untrained participants already achieve 70 percent precision, targeted training might push detection closer to the 6.9-centimeter theoretical maximum.

Sensory systems exhibit extraordinary plasticity—Braille readers and London taxi drivers are classic examples. Biohackers may pursue structured training regimens to enhance remote touch, measuring progress via signal detection metrics. Success could benefit fields from archaeology to search operations to wilderness survival.

From Landmine Detection to Submarine Navigation

Landmines injure thousands yearly, and existing detection systems often fail in cluttered or non-metallic environments. Remote touch could enable scanning robots that detect mines mechanically rather than electromagnetically, reducing false positives and improving safety.

The five-centimeter plastic cube used in the study approximates the size of many anti-personnel mines, making the technique directly relevant. In underwater environments, where visibility is low and sediment clouds sensors, tactile remote detection could help submarines and underwater robots identify buried hazards or objects on the seafloor.

A Breakthrough for Blind Navigation Technologies

More than two billion people worldwide experience visual impairment, relying on canes, guide dogs, or haptic devices for safe travel. Existing systems detect above-ground obstacles but struggle with uneven surfaces, debris, or ground-level hazards.

Remote touch–based sensors embedded in canes or mobility robots could warn users of changes in terrain several centimeters ahead. Because blind individuals often develop heightened tactile processing and may recruit visual cortex for touch, they might excel at interpreting remote touch signals—an unexplored but promising avenue for assistive research.

Philosophy Confronts a Crisis of Embodimen

Philosophers of perception have long argued that touch defines the boundary between self and world. Remote touch dissolves this line, proving that the body’s sensory field can extend several centimeters into surrounding material.

The discovery supports theories of embodiment and extended cognition, suggesting perception is distributed across the body and environment rather than confined to skin or brain. If granular media act as an extension of the tactile organ, traditional distinctions between internal and external perception must be reconsidered within consciousness studies.

Why a 12-Person Study May Still Be Robus

At first glance, twelve participants may seem insufficient. Yet each person completed 18 attempts, producing 216 trials—enough for strong statistical power given the large effect size. The sensitivity measure d′ of 1.1973 indicates clear separation between signal and noise.

Results were consistent across individuals, and robotic replication independently confirmed the underlying mechanics. Still, essential questions remain: how do age, sex, or blindness affect performance? Larger and more diverse samples are needed to determine whether remote touch is universal or variable across populations.

What Other Human Senses Have We Missed?

Remote touch’s late discovery raises an obvious question: what else can humans do that science hasn’t yet tested under the right conditions? Past centuries added balance, proprioception, interoception, and more to our sensory catalog. Some researchers argue there may be over thirty distinct subsystems today.

Perhaps humans can detect objects in other granular media, interpret water-borne pressure waves, or identify chemical plumes before odor molecules reach receptors. The Queen Mary study’s interdisciplinary approach—physics, behavioral testing, and robotics—offers a roadmap for uncovering hidden sensory layers still waiting to be revealed.

The Sense That Redefines What It Means to Be Human

The November 2025 discovery that humans possess remote touch—detecting objects through sand up to 6.9 centimeters away—represents a scientific turning point. It overturns millennia of assumptions about touch, challenges philosophical boundaries of the body, and opens immediate applications in robotics, planetary exploration, archaeology, and safety.

With a d′ of 1.1973 and strong human-robot validation, this new sense is now firmly established. As researcher Elisabetta Versace observed, the finding fundamentally reshapes our understanding of perception—and expands the very definition of what humans are capable of.