For 24 years, it sat in darkness. A nearly complete skeleton, locked in a Canadian museum’s storage, unnamed, waiting. In 2001, fossil collector Chris Moore found these bones near Golden Cap in Dorset. But nobody realized they were extraordinary.

Not until 2025. Not until Dr. Dean Lomax pulled it from the archives and recognized what had been hiding in plain sight: a creature that rewrites 190 million years of history. Welcome to Xiphodracon goldencapensis—the “Sword Dragon” that changed everything.

The Moment Everything Changed

October 2025. A research paper drops in Papers in Palaeontology. Scientists pause. A new genus. From the UK’s Jurassic Coast. The first entirely new Early Jurassic ichthyosaur was discovered there in more than 100 years.

Thousands of fossils have been recovered since Mary Anning’s era in the 1800s, yet nothing like this has been found in a century.

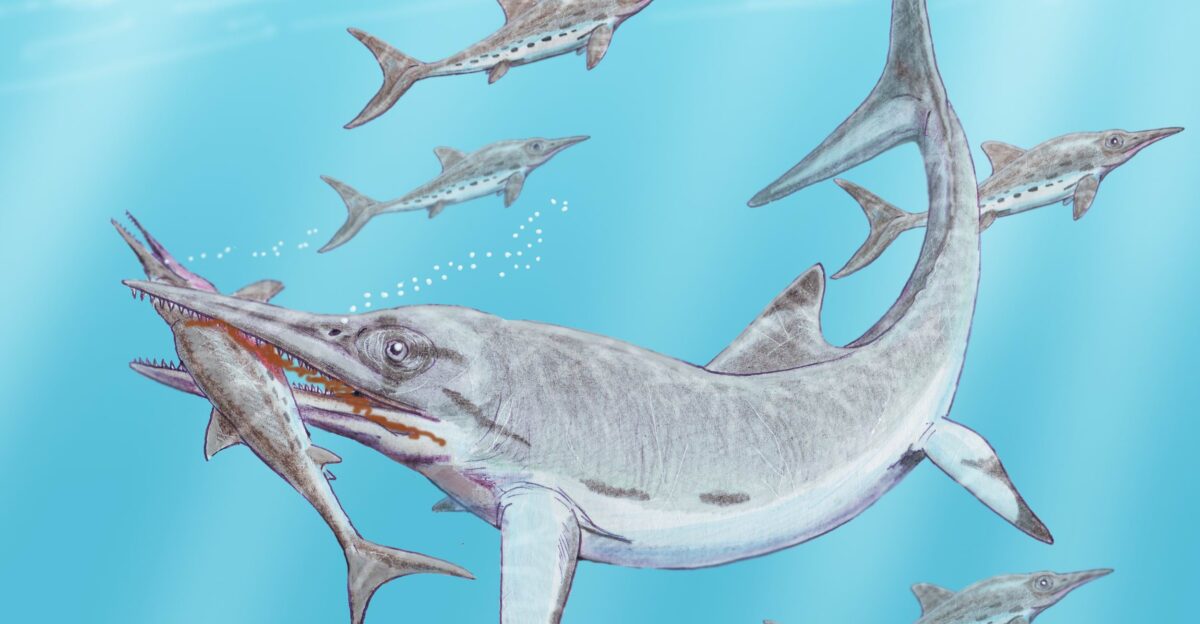

A Predator, 3 Meters Long, Built to Kill

A marine reptile, roughly the length of a modern sports car, gliding through Jurassic seas, its snout stretches long and narrow—sword-like, lined with needle-sharp teeth. But the real marvel is its eyes. Enormous. Disproportionately massive eye sockets suggest a creature hunting in twilight waters, relying on exceptional vision.

Fish. Squid. Soft-bodied prey wouldn’t stand a chance. Scientists see traces of its last meal preserved in the ribcage.

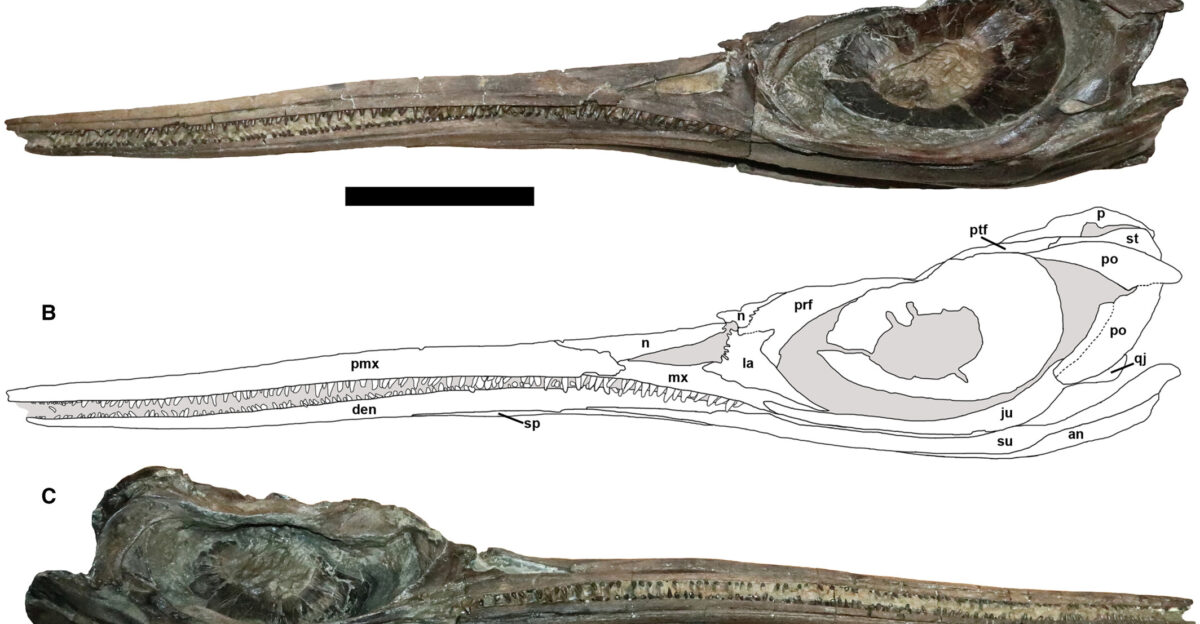

The Skull Tells a Story of Violence

Look closely at the skull, and you see bite marks. Unmistakable wounds from a much larger predator—likely a massive Temnodontosaurus stretching beyond 30 feet. This 10-foot creature survived injury, survived disease, as evidenced by malformed limb bones and teeth, and then met its end in catastrophic violence.

Life in ancient oceans was hierarchical and brutal. Apex predators were themselves hunted. This fossil preserves not just anatomy but a final moment—when this sword dragon’s reign ended. Death written in stone.

Why This Discovery Matters

Shift perspective. The real significance isn’t just about one creature. It’s about what that creature reveals about an entire epoch. The Pliensbachian period—193 to 184 million years ago—witnessed something paleontologists have long puzzled over: complete faunal turnover. Old ichthyosaur families disappeared. Entirely new families emerged

. The two groups shared zero species in common. It was like watching one world end and another begin. Yet the fossil record from this interval is maddeningly sparse. Scientists had theories but lacked evidence. Until now.

A Gap in the Fossil Record, Finally Filled

Professor Judy Massare of SUNY Brockport explains: “Thousands of complete ichthyosaur skeletons are known from before and after the Pliensbachian. The two faunas are quite distinct, with no species in common. Clearly, a major change occurred.” But when?

The Pliensbachian itself yielded almost nothing—incredibly rare fossils, frustratingly incomplete. Like reading a book with the middle chapter missing. Xiphodracon changes that.

One Specimen, One Chance to Understand

This isn’t just another fossil. This is the only known specimen of Xiphodracon goldencapensis. Ever. One skeleton. One chance to understand an entire species. That places extraordinary weight on this single find. The most complete ichthyosaur ever recovered from the Pliensbachian period—preserved in three dimensions, not flattened.

Skull intact. Vertebrae articulated. Limb bones aligned. Traces of the last meal preserved.

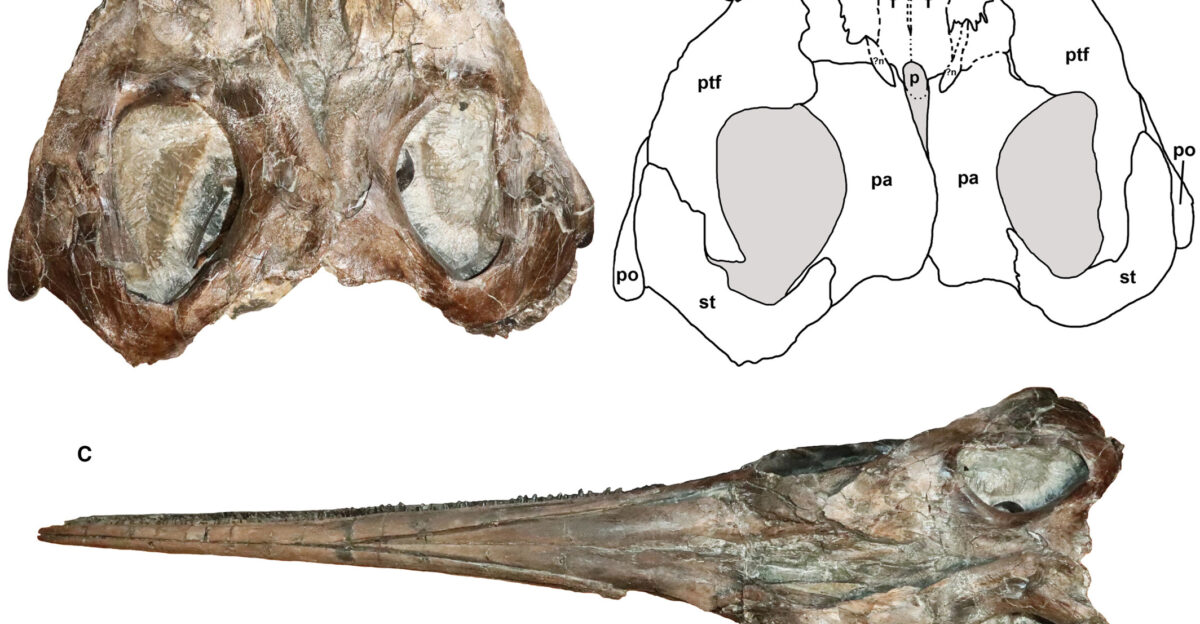

The Three-Dimensional Advantage: Seeing in Full

Photo by D R Lomax J A Massare E E Maxwell on Wikimedia

Three-dimensional preservation is rare. Most ancient skeletons get crushed, flattened under geological pressure into pancakes. But Xiphodracon was locked in stone and time in full form. This changes everything. Scientists can rotate the specimen, examine it from every angle, and understand how bones articulated in life.

They identify unique anatomical features that two-dimensional fossils would hide forever. They reconstruct biomechanics—how it moved through water, how it hunted, how it lived.

Unique Features Never Seen Before

The fossil revealed something completely unexpected: an unusual bone structure around the nostril. This lacrimal bone bears prong-like bony structures, unlike anything paleontologists had ever observed in any other ichthyosaur.

These autapomorphies—unique, one-of-a-kind features—suggest Xiphodracon occupied an evolutionary niche all its own. It wasn’t just another ichthyosaur. It was genuinely different.

The Early Jurassic Revolution

Here’s what Lomax’s team discovered: Xiphodracon is more closely related to species that came later, in the Toarcian period. This single skeleton allowed paleontologists to pinpoint when the faunal turnover actually happened—much earlier in the Pliensbachian than previously suspected.

The old families didn’t linger. The new families didn’t gradually replace them. The transition was sharp, decisive, and earlier than expected.

Two Ichthyosaur Worlds With Nothing in Common

Imagine two completely separate oceanic ecosystems, separated by mere millions of years, yet sharing not a single species. That’s the Pliensbachian division. The creatures that hunted before this period—gone. Replaced by entirely different families, different body plans, different strategies.

It’s not a gradual replacement. It’s a radical reorganization. Xiphodracon exists in that liminal space—connected to what came after, showing us what that transition looked like from the inside.

The Hunt Across Centuries

England’s Jurassic Coast has yielded ichthyosaur fossils for over 200 years. Mary Anning, the pioneering fossil hunter, made her first discovery at age 12 in 1811. Since then, thousands upon thousands of marine reptile remains have emerged from those cliffs and beaches.

Yet finding an entirely new genus from the Early Jurassic took another full century after Anning’s era.

The 24-Year Sleep

From 2001 to 2016, the skeleton sat in the museum’s collection, unstudied. It wasn’t neglect—it was the reality of paleontology. Thousands of specimens arrive annually. Museums lack staff to examine every fossil immediately. Preparation takes time. Analysis takes longer.

In 2016, Dr. Lomax encountered this specimen. He recognized something unusual. Something different. Something that didn’t fit neatly into known categories. He suspected. He studied. He collaborated. By 2025, nine years of careful research culminated in the formal identification of a new genus.

From Dorset Cliffs to a Toronto Museum

The skeleton’s journey is almost as remarkable as its anatomy. Discovered on the English coast. Purchased by a Canadian institution. Examined by an international research team: Dr. Lomax at Manchester and Bristol, Professor Massare at SUNY Brockport, and Dr. Erin Maxwell at Stuttgart.

Modern paleontology transcends borders. A cast was made for Stuttgart. The original remains in Toronto.

The Pliensbachian Problem

The Pliensbachian period spans roughly 9 million years. A blink in geological time. Yet this interval holds outsized importance for ichthyosaur evolution. It’s when the old guard vanished, and new powers rose. But here’s the infuriating part: the fossil record is sparse.

“Ichthyosaurs are exceedingly rare during this era,” Dr. Lomax notes. Each Pliensbachian specimen becomes a treasure.

The Teeth Tell Tales: Precision Predator

The name itself is deliberate. Xiphos—sword. Drakōn—dragon. Ancient Greek origins chosen specifically for what this creature was: a sword-wielding marine dragon. Those needle-like teeth weren’t random. They represent millions of years of evolutionary refinement for a specific prey type.

Combined with enormous eyes—designed for hunting in dim waters—and that distinctive sword-like snout, Xiphodracon was a precision instrument. Not a generalist feeding on anything. A specialist.

What the Fossil Reveals About Ocean Life

Dr. Erin Maxwell emphasizes the broader significance: “This skeleton provides critical information for understanding ichthyosaur evolution, but also contributes to our understanding of what life must have been like in the Jurassic seas of Britain.”

It shows us predator-prey dynamics. It shows us predation risk—even apex predators got eaten. It shows us disease and injury. It shows us survival strategies. It shows us death. One fossil becomes a window into an entire ecosystem’s reality.

Plans for Public Display: The Dragon Emerges

Soon, the “Sword Dragon of Dorset” will emerge from museum archives into public view. Plans are underway to display Xiphodracon at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. When you stand before that fossil, you won’t see an abstract scientific specimen.

You’ll see a real creature that really existed, really hunted, really died violently, and really waited 190 million years to tell its story.

The Research Continues

But the work doesn’t end with publication. The research team continues analyzing. Those mysterious prong-like structures on the lacrimal bone? Still being studied. What was their function? Biomechanical models are being developed.

How did Xiphodracon move through water? What was its hunting efficiency? How does it relate to later ichthyosaurs that survived longer?

The Missing Piece, Finally in Place

Dr. Lomax summarized it perfectly: “This time is pretty crucial for ichthyosaurs as several families went extinct and new families emerged, yet Xiphodracon is something you might call a ‘missing piece of the ichthyosaur puzzle.'” One fossil. One perfectly preserved skeleton from a poorly understood epoch. One creature that waited 24 years to be recognized.

The past speaks when we listen carefully enough. The Sword Dragon was waiting. It just took 190 million years, one curious collector, and one observant scientist to finally hear what it had been saying all along.

Sources:

Lomax, D. R., Massare, J. A., & Maxwell, E. E. (2025). “A new long and narrow-snouted ichthyosaur illuminates a complex faunal turnover during an undersampled Early Jurassic (Pliensbachian) interval.” Papers in Palaeontology, October 9, 2025.

University of Manchester. (2025). “Rare Jurassic ‘Sword Dragon’ prehistoric reptile discovered in the UK.” October 27, 2025.

BBC News. (2025). “Fossil found on UK coast is unique ‘sword dragon’ species.” October 9, 2025.

Everything Dinosaur. (2025). “Dorset fossil fills an important gap in ichthyosaur evolution.” October 9, 2025.

New Scientist. (2025). “‘Sword Dragon’ ichthyosaur had enormous eyes and a lethal snout.” October 9, 2025.

Oxford University Museum of Natural History. “Mary Anning’s Ichthyosaur.”