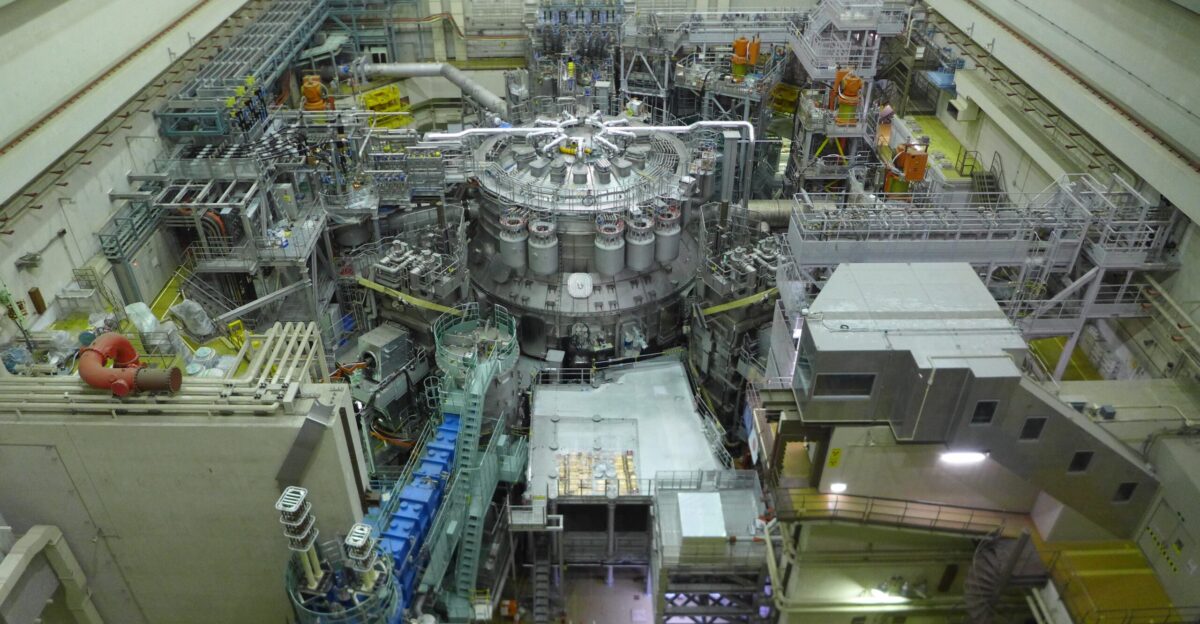

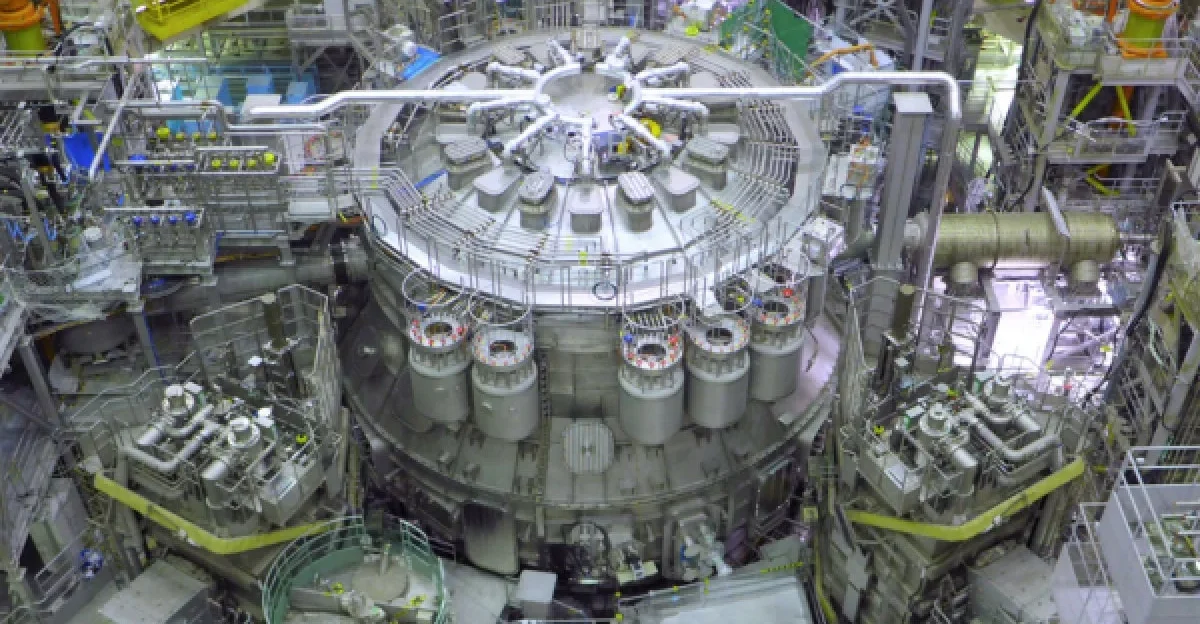

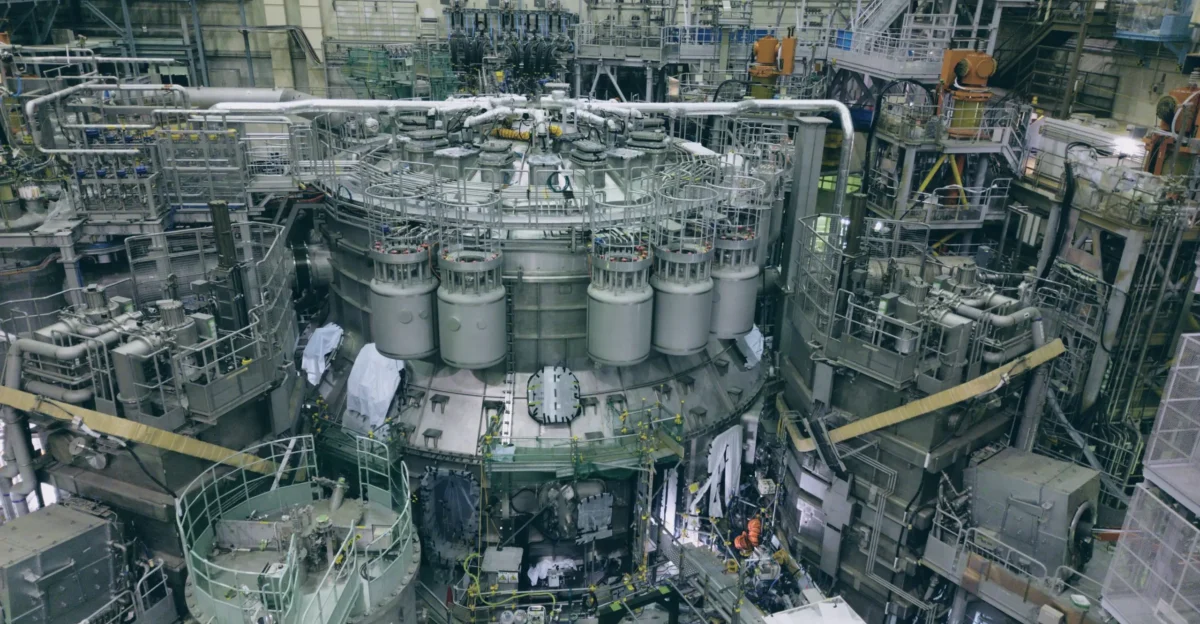

Japan’s JT‑60SA tokamak is currently the world’s largest fusion reactor by plasma volume, with 160 m³ verified by Guinness World Records in Naka, Ibaraki, on 4 September 2024. Built by Japan’s QST and Europe’s Fusion for Energy for about €600 million, it is designed to confine plasma near 200 million °C using 41 MW of heating power. After first plasma in October 2023, the machine entered a planned 2–3‑year shutdown to upgrade external heating and diagnostics ahead of higher‑power campaigns later in the decade—a strategic reset, not a breakdown.

History: fusion as a century‑scale project

The JT‑60SA pause only makes sense in fusion’s 100‑year story. Arthur Eddington linked starlight to hydrogen fusion in the 1920s, and magnetic‑confinement research accelerated after the Soviet tokamak concept in the 1950s.

Devices like the UK’s Joint European Torus (JET) spent decades learning to stabilize plasmas, culminating in a 69‑megajoule, 5.2‑second deuterium‑tritium pulse in 2023 before final shutdown. JT‑60SA itself stems from a 2007 Europe–Japan “Broader Approach” agreement, with assembly progressing through the 2010s and first plasma only in late 2023, so a focused 2–3‑year upgrade window is proportionate.

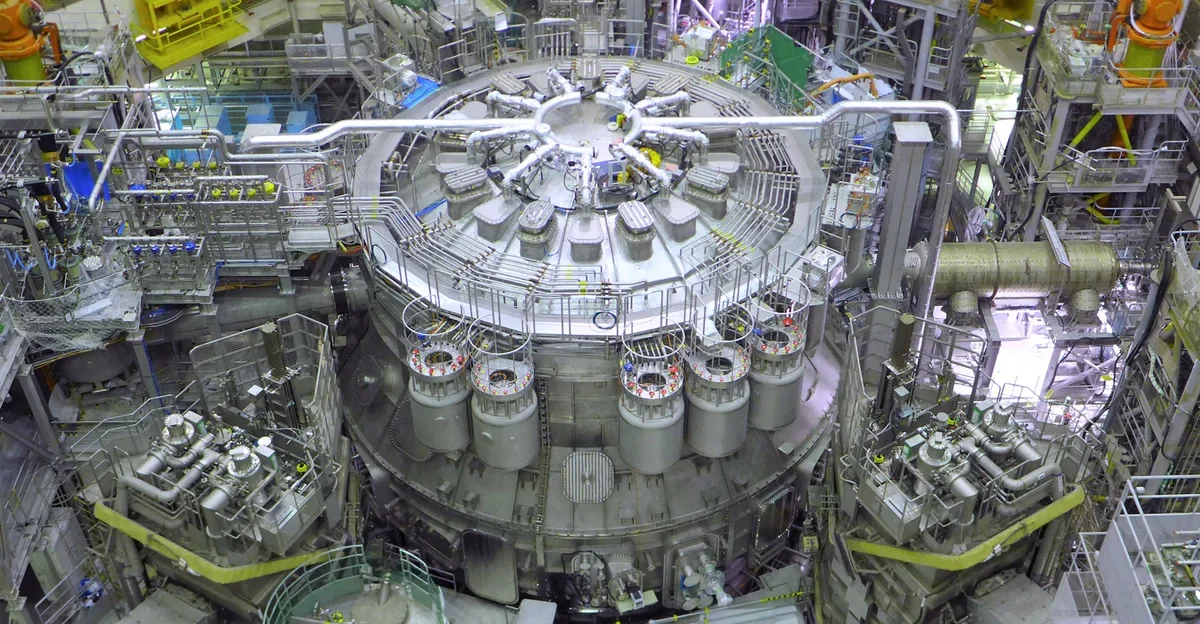

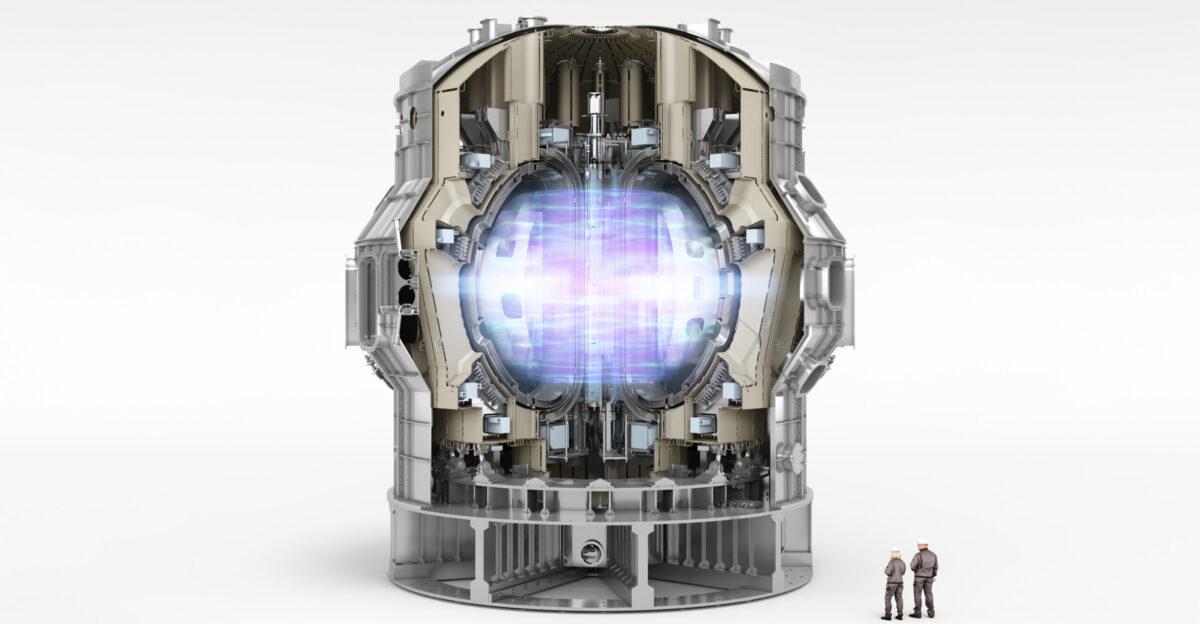

The machine: creating star conditions in a tokamak

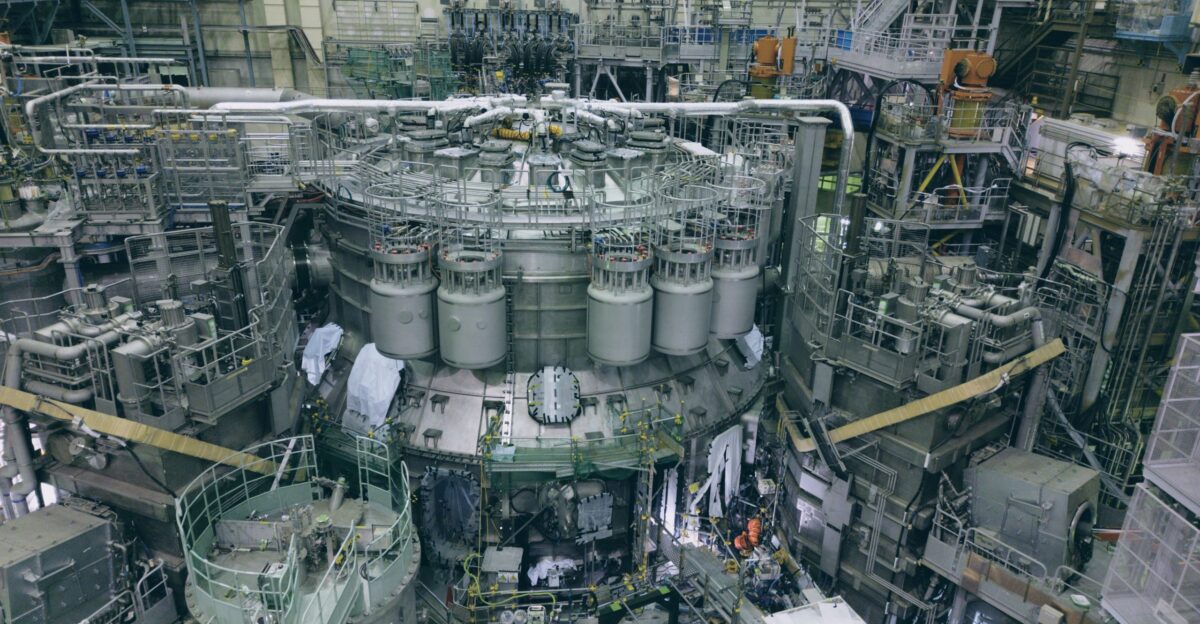

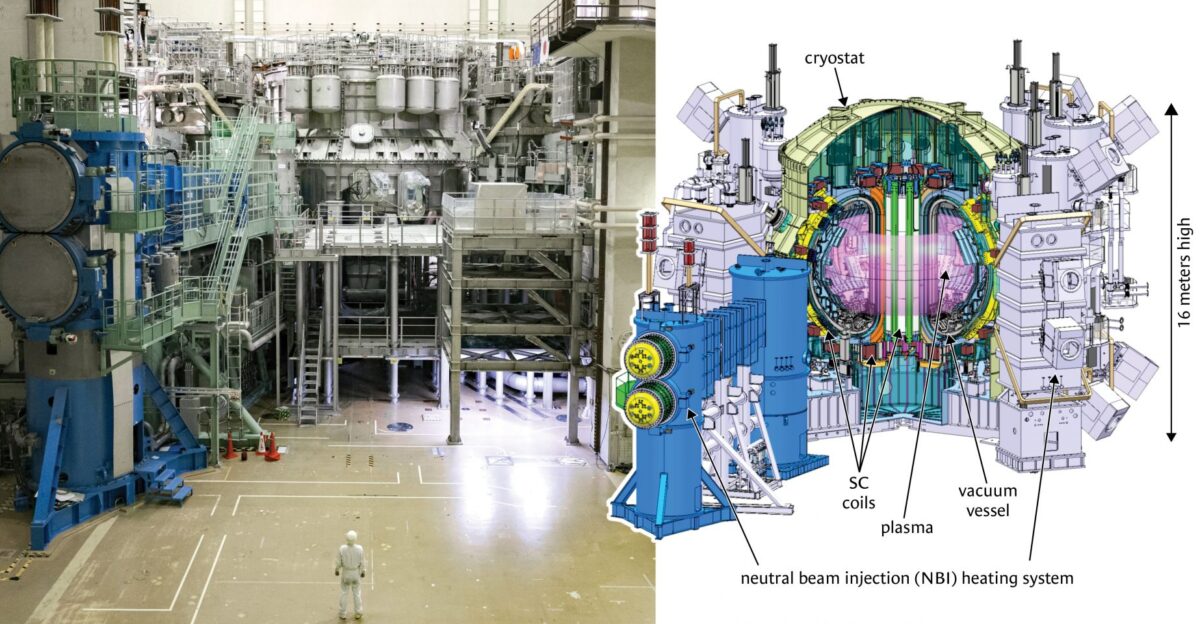

JT‑60SA is a six‑storey superconducting tokamak built as ITER’s “satellite,” using powerful toroidal and poloidal magnetic fields to confine ultra‑hot plasma inside a doughnut‑shaped vacuum vessel. Its coils operate around 4 K (about −269 °C), while the plasma can reach of order 100–200 million °C, generating a vast temperature gradient managed within a hall northeast of Tokyo.

The design allows up to roughly 41 MW of heating and current drive for long pulses, enabling studies of advanced plasma regimes directly relevant to ITER and future DEMO‑class reactors. Operating at these extremes demands reliability at the limits of materials, cryogenics, and power electronics, justifying serious mid‑course upgrades.

Record status: Guinness recognition with scientific weight

Guinness World Records confirmed that JT‑60SA’s plasma volume of 160 m³, verified on 4 September 2024, made it the largest tokamak in the world, surpassing the previous 100 m³ record.

QST and partners marked this recognition in October 2024, using the moment to highlight the reactor’s role as a test‑bed for ITER and DEMO. EUROfusion and ITER documents stress that ITER’s plasma will be about six times larger, underscoring that JT‑60SA is a scaled prototype rather than a power plant. When a record‑holding device pauses to retool, it reflects disciplined iteration toward more demanding physics, not retreat.

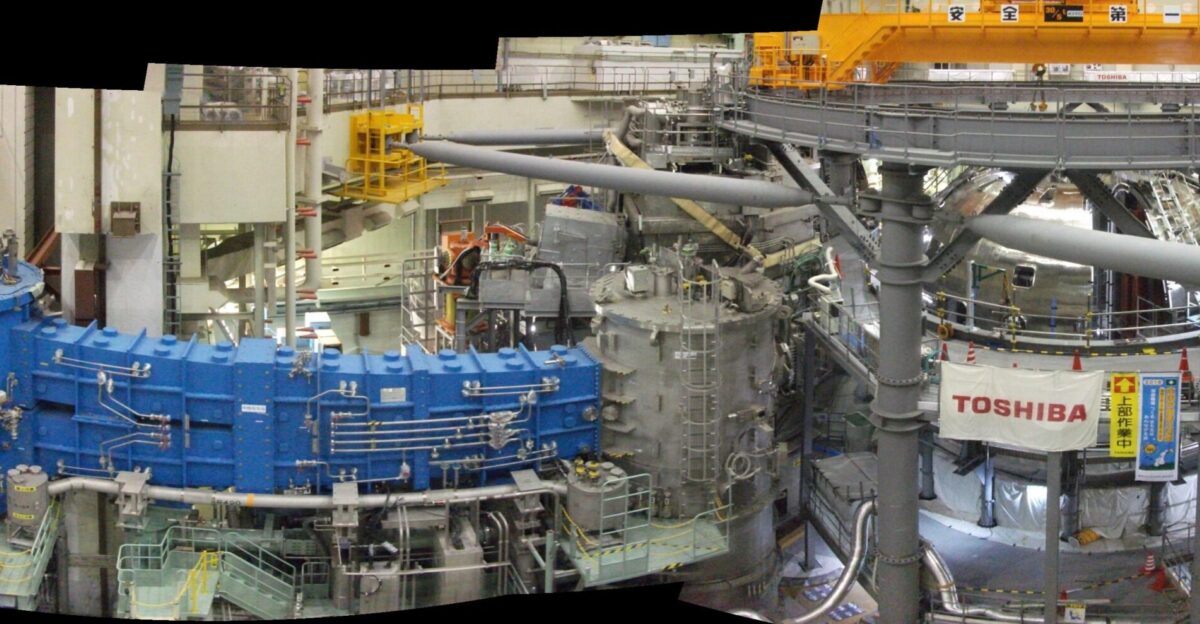

Collaboration: 170 labs, 29 countries, and shared risk

JT‑60SA sits at the center of a broad international network: EUROfusion alone connects around 170 laboratories and industrial partners from 29 European countries, many contributing components and staff to the project. Reports indicate several hundred researchers from Europe and Japan, plus more than 70 suppliers, were involved in constructing and commissioning the machine.

The device is a pillar of the EU–Japan “Broader Approach” collaboration alongside ITER, meant to accelerate fusion development and train new experts. In such a transgenerational program, a multi‑year, agreed shutdown helps align priorities, schedules, and risk appetite across institutions that expect to work together for decades.

Why the shutdown is strategically rational

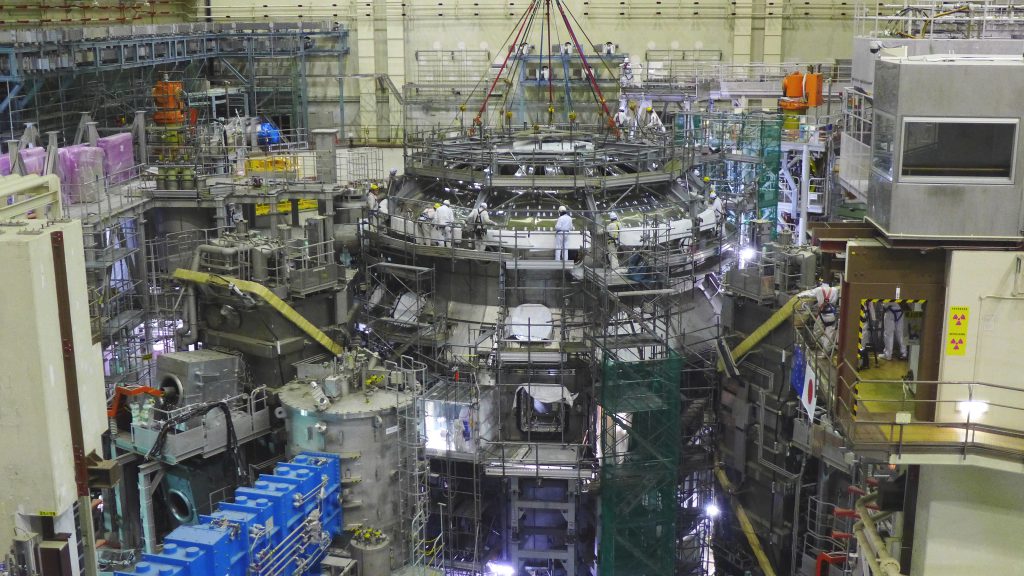

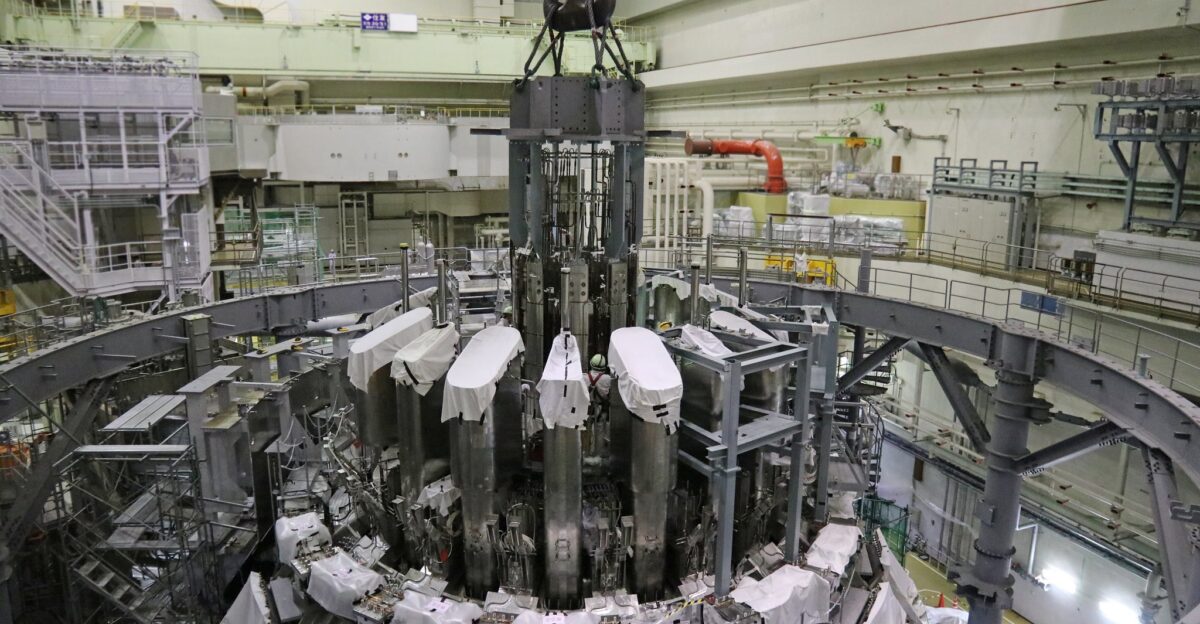

After first plasma in October 2023, integrated commissioning confirmed that JT‑60SA’s main systems functioned, but also highlighted the need to install additional heating, diagnostics, and protection hardware before entering high‑power operation.

Fusion for Energy and QST describe the current phase as fitting “many key components” to prepare a more capable configuration for subsequent experimental campaigns. Large‑scale engineering efforts often fail through cumulative trade‑offs rather than a single error; a deliberate 2–3‑year pause openly rejects the “build while flying” mindset and treats JT‑60SA as an industrial‑grade prototype whose configuration should be optimized before real stress‑testing.

Safety, risk, and public legitimacy

Fusion reactors differ fundamentally from fission plants: they hold much less fuel, cannot sustain chain reactions, and primarily pose engineering challenges related to heat loads, neutron damage, and cryogenics. Even so, a major incident at JT‑60SA would carry political consequences, particularly in Japan, where nuclear risk perceptions remain strongly shaped by the 2011 Fukushima accident.

In March 2021, the “EF1 feeder incident” caused a short circuit, damaging current feeder joints and leading to helium leakage that demanded repairs at many locations before commissioning could continue. Against that history, insisting on a thorough upgrade and testing phase before more aggressive plasmas is not over‑cautious—it is essential to maintain public trust and regulatory confidence.

Economic logic: extracting maximum value from a €600M asset

JT‑60SA, with construction costs of roughly €600 million, is an experimental facility with a planned multi‑decade role in the fusion roadmap, not a disposable prototype. Its economic value lies in the quality of the physics and engineering insights it delivers for ITER and future DEMO‑class plants, not in brief headline‑grabbing shots.

Upgrading heating and diagnostics to fully exploit the 160 m³ plasma and 41 MW capability enables systematic exploration of advanced scenarios, stability boundaries, and component lifetimes that older machines cannot access. A 2–3‑year pause early in operation is a relatively low‑cost way to increase learning per experiment, improving the return on decades of public investment.

Systems thinking: JT‑60SA as ITER’s forward scout

ITER, under construction in southern France, will be roughly twice JT‑60SA’s size with about six times the plasma volume, making experimental missteps there extremely expensive. JT‑60SA is explicitly tasked with testing operational scenarios, plasma shapes, and control schemes that inform ITER’s procedures before ITER reaches full deuterium–tritium operation.

Allowing the “scout” device to pause for hardware and software enhancements, then probe more challenging operating regimes first, reduces risk for ITER’s multibillion‑euro campaign. In practice, JT‑60SA’s shutdown and upgrade period acts as a safety and optimization buffer for the wider fusion program, improving the design basis for any later commercial plants.

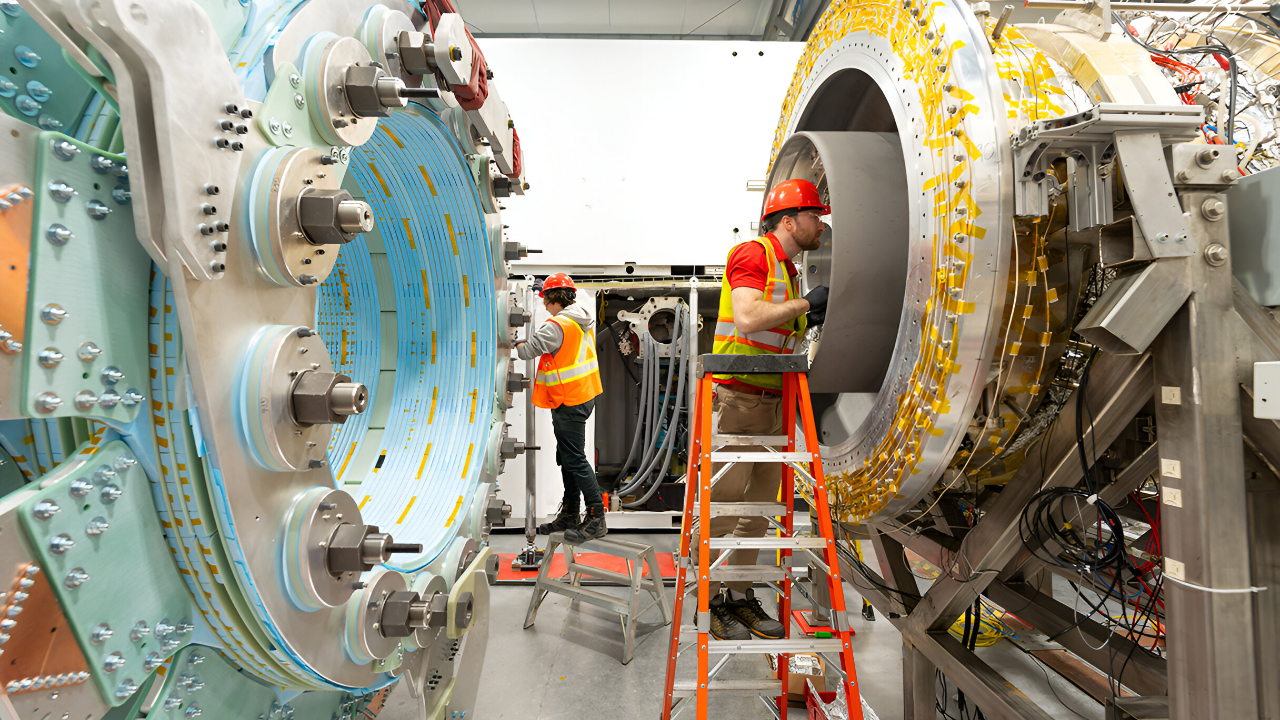

Technology deep‑dive: heating and control systems

Research plans show JT‑60SA designed for up to about 41 MW of combined heating and current drive, using neutral beam injection and electron cyclotron resonance heating to drive long plasma pulses on the order of 100 seconds.

Achieving reactor‑relevant conditions requires flexible, reliable heating to reach high temperatures, shape current profiles, and sustain plasmas with significant bootstrap current fractions. The upgrade window enables new heating modules, improved machine protection, and fast diagnostics that support advanced control algorithms, including real‑time management of instabilities such as edge‑localized modes. These capabilities are central to any realistic path toward net‑energy steady‑state fusion, so strengthening them now directly supports credible 2040s–2050s deployment timelines.

Workforce and knowledge transfer: turning downtime into training time

Global fusion progress depends heavily on a small pool of specialists in superconducting magnets, high‑heat‑flux components, plasma control, and nuclear regulation. JT‑60SA’s upgrade phase brings together QST, F4E, EUROfusion partners, and industrial suppliers for complex integration tasks, effectively creating a real‑world training platform for these scarce skills.

Engineers and scientists are learning to diagnose faults, redesign systems, and recommission a large superconducting tokamak under operational constraints that resemble those future plants will face. That experience bank increases resilience: when ITER or DEMO encounter similar problems, a distributed community will already have practical solutions derived from JT‑60SA’s challenges and fixes.

Climate realism: late but still necessary

Assessments from international agencies suggest that fusion will not provide large‑scale electricity to grids before the 2040s or 2050s, well after current 2030 climate targets. This delay invites criticism that fusion distracts from rapidly deployable options like wind, solar, and storage.

However, long‑term decarbonization scenarios often require firm, low‑carbon capacity to complement variable renewables, especially beyond mid‑century. In that context, rushing devices like JT‑60SA for short‑term optics would be counterproductive; robust, carefully validated experiments are needed now to create mature, bankable fusion technologies ready to support a deeply decarbonized system later.

Geopolitics and energy security: building a shared playbook

Secure access to abundant, low‑carbon baseload energy is a strategic objective for many states. ITER already involves 35 countries as full or associate members, including the EU, Japan, the United States, China, Russia, India, and others. JT‑60SA, led by Europe and Japan, broadens this framework by fostering shared standards, supply chains, and operational know‑how across allied nations rather than concentrating capability in a single country.

The shutdown and upgrade period, which coordinates new components from multiple suppliers and regions, serves as a rehearsal for future cross‑border fusion industries that will construct and maintain commercial plants. Getting this cooperative architecture right is as strategically important as any individual experiment, because it shapes who writes the rules for 21st‑century energy security.

Counterfactuals: the real risk of rushing

If operators pushed JT‑60SA into extended, higher‑power campaigns without fully mature heating and diagnostic systems to “save” time, they would increase the odds of hardware damage and unreliable data. The EF1 feeder incident in 2021—where inadequate insulation led to an electrical fault, helium leaks, and the need for extensive repairs—demonstrated how much disruption one technical problem can cause even before routine plasma operation.

A similar or worse event under more demanding conditions could force an unplanned, longer shutdown, weaken public confidence, and reduce political support for large fusion projects, including ITER. Compared with that scenario, a controlled 2–3‑year upgrade window is an intentional, limited delay designed to avoid chaotic, reputation‑damaging failures.

Conclusion: a deliberate slowdown on the only credible path

Seeing the world’s largest tokamak pause for 2–3 years soon after a €600M construction effort is emotionally unsettling, especially amid climate and energy anxiety. Yet JT‑60SA’s verified status—a 160 m³ Guinness‑certified plasma volume, first plasma in October 2023, integration into EUROfusion and ITER roadmaps—shows that the shutdown is a planned step in a carefully staged program.

Upgrading heating, diagnostics, and integration now converts the device into a more powerful research engine, a training hub, and a risk‑reduction platform for ITER and future DEMO plants. For anyone serious about fusion contributing to energy systems in the 2040s–2050s, that controlled pause is not a setback but a necessary investment in reliability and credibility.