In Burlington, North Carolina, the wastewater infrastructure designed to protect the environment was secretly poisoning it. For years, regulators were baffled as water leaving the treatment plant contained significantly higher levels of toxic PFAS than the sewage entering it. This contradiction defied standard environmental science. The culprit wasn’t a simple illegal discharge, but a complex chemical interaction that turned harmless industrial runoff into one of the most potent toxins known to nature—right inside the treatment plant itself.

The Investigation: Tracking a Ghost Chemical

Duke University’s monitoring network, funded by $5 million from the state, began tracking this anomaly in 2018. While most systems showed typical filtration results, Burlington, Pittsboro, and Chapel Hill emerged as alarming outliers. By 2025, scientists had solved the puzzle. The spikes weren’t coming from traditional PFAS compounds, but from “fluorinated polymer nanoparticles”—microscopic industrial ingredients used in textile finishes. These particles were effectively invisible to standard testing methods, allowing them to pass undetected through regulatory checkpoints for years.

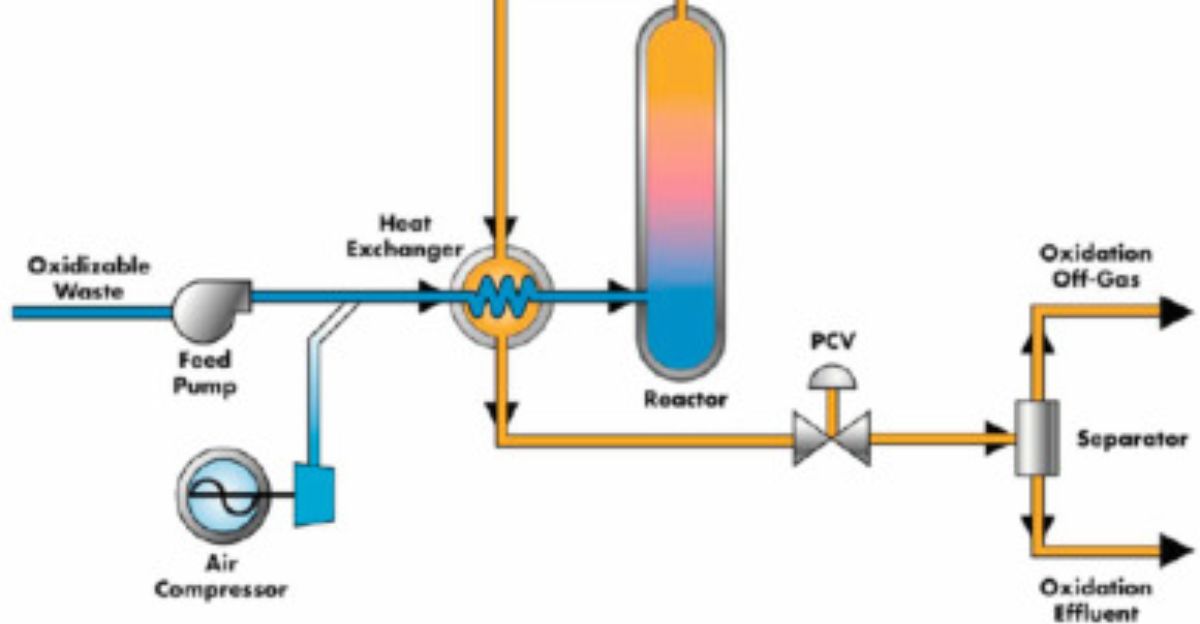

The Catalyst: How Thermal Treatment Backfired

The smoking gun was found in Burlington’s “Zimpro” system, a thermal treatment process designed to break down heavy waste using high heat and pressure. Instead of destroying the pollutants, this intense energy fractured the stable nanoparticle side-chains. This chemical violence transformed inert polymer particles into regulated, mobile, and highly toxic PFAS compounds. The scale of this transformation was staggering, generating contamination levels approximately three million times higher than the EPA’s safety limits for drinking water.

Unprecedented Amplification: The Lab Confirmation

To prove this theory, Duke researcher Patrick Faught recreated the plant’s conditions in a laboratory. The results were terrifying: when the benign wastewater precursors were subjected to Zimpro-like heat and pressure, PFAS levels surged by 50,000 to 80,000 percent. The created toxins were so potent that they contaminated laboratory equipment for over a week. This experiment confirmed that the treatment plant was not merely a passive victim of pollution, but an active, unintentional manufacturer of hazardous chemicals.

The Hidden Source: Unmasking the Polluter

Identifying the specific industrial source required a breakthrough in forensic chemistry. Because standard tests couldn’t see the nanoparticles, researchers had to simulate the treatment process on upstream samples to trigger the spike. This method exposed wastewater from Elevate Textiles as a primary source. The facility had been discharging massive loads of these “invisible” precursors legally. Once identified, legal and regulatory pressure forced swift changes, including the elimination of PFAS products by Unichem and reductions by Shawmut, halting new contamination.

The Long-Term Reservoir: Poisoned Soil

The damage extends far beyond the river water. Like many utilities, Burlington converts wastewater sludge into “biosolids” fertilizer for local farms. Because the precursor nanoparticles accumulated in this sludge, they were spread across acres of agricultural land. Over time, these particles degrade into soluble PFAS, leaching into groundwater and crops for decades. This mechanism explains why Chapel Hill, despite being outside the direct discharge path, still suffers from contamination—the pollution is now embedded in the watershed’s soil itself.

The Human Cost: A Public Health Failure

The consequences of this regulatory blind spot are measured in human health. Residents in Pittsboro, who rely on the Haw River for drinking water, show elevated PFAS levels in their blood. This chronic exposure correlates with severe risks, including kidney cancer, thyroid disease, and immune suppression. The failure here was systemic: agencies tested only for known compounds, missing the precursors entirely. This allowed a decade of toxic loading that will likely impact the health of thousands across the Cape Fear basin.

National Implications: A Warning for the Industry

Burlington is likely just the first documented case of a widespread national vulnerability. Textile manufacturing and thermal treatment systems exist together in many industrial watersheds across the United States. Since most regulators still do not test for these precursors, it is statistically probable that similar “invisible” pollution is occurring elsewhere. Without a pivot in policy to detect and control precursor chemicals, other communities may remain unaware that their water treatment infrastructure is actively amplifying toxic threats.

Sources

- Duke University Pratt School of Engineering – “Uncovering the Source of Widespread ‘Forever Chemical’ Contamination in North Carolina”

- LabCompare – “Source of Widespread PFAS Contamination Discovered in North Carolina”

- IFLScience – PFAS discovery in North Carolina’s Piedmont region

- Duke PFAS Exposure Study – NC Piedmont drinking water and blood levels

- NC Health News – Pittsboro residents’ PFAS blood levels

- NIEHS – PFAS health effects overview

- ACS Environmental Science & Technology Letters – research on colloidal side-chain fluorinated polymer nanoparticles

- Waterkeepers Carolina – “Forever Chemicals (PFAS) in NC Waterways”