In November 2025, researchers at Queen Mary University of London and University College London announced a discovery that challenges centuries-old assumptions about human perception: people can sense objects buried in sand before making physical contact. This finding, rooted in rigorous experimentation and signal detection analysis, not only redefines the boundaries of touch but also opens new avenues for technology, safety, and education.

Rethinking the Limits of Human Senses

For over two millennia, Western science has largely accepted Aristotle’s claim that humans possess only five senses—sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch. This framework has shaped education and scientific inquiry, even as modern neuroscience has identified additional sensory systems like proprioception and balance. The new research overturns a core Aristotelian assumption: that touch requires direct skin contact. In controlled trials, twelve adults swept their fingers through dry sand, searching for a hidden five-centimeter plastic cube. Remarkably, participants detected the object before touching it in 79 out of 216 trials, with an average detection distance of 2.7 centimeters and over 70 percent accuracy. Theoretical modeling suggests the maximum possible distance is 6.9 centimeters, indicating humans operate at about 39 percent of the physics-defined limit. This evidence demonstrates that humans can perceive objects through granular materials without direct contact, demanding a broader, multisensory model of perception.

The Physics Behind Remote Touch

The mechanism enabling this “remote touch” lies in the physics of granular media. As a finger moves through sand, it generates subtle mechanical disturbances that travel through the grains. When these waves encounter a buried object, they reflect altered patterns back toward the finger. Human mechanoreceptors—specialized nerve endings in the skin—are sensitive enough to detect these changes. The study’s results closely matched physics-based predictions, with observed detection distances aligning with the theoretical maximum. This ability, previously undocumented in primates, reveals a latent human capacity to interpret mechanical signals transmitted through loose materials.

Comparing Human and Robotic Sensing

To explore the potential of this sensory ability, the research team developed a robotic tactile probe equipped with advanced neural networks. In 120 trials, the robot achieved perfect detection at greater distances—up to nearly 13 centimeters—though it also produced more false positives than human participants. While machines excelled at raw sensitivity, humans demonstrated superior judgment, likely integrating subtle cues that current artificial systems cannot fully interpret. This interplay between biological and artificial sensing highlights the complementary strengths of each and suggests that future technologies could benefit from mimicking or enhancing human perceptual strategies.

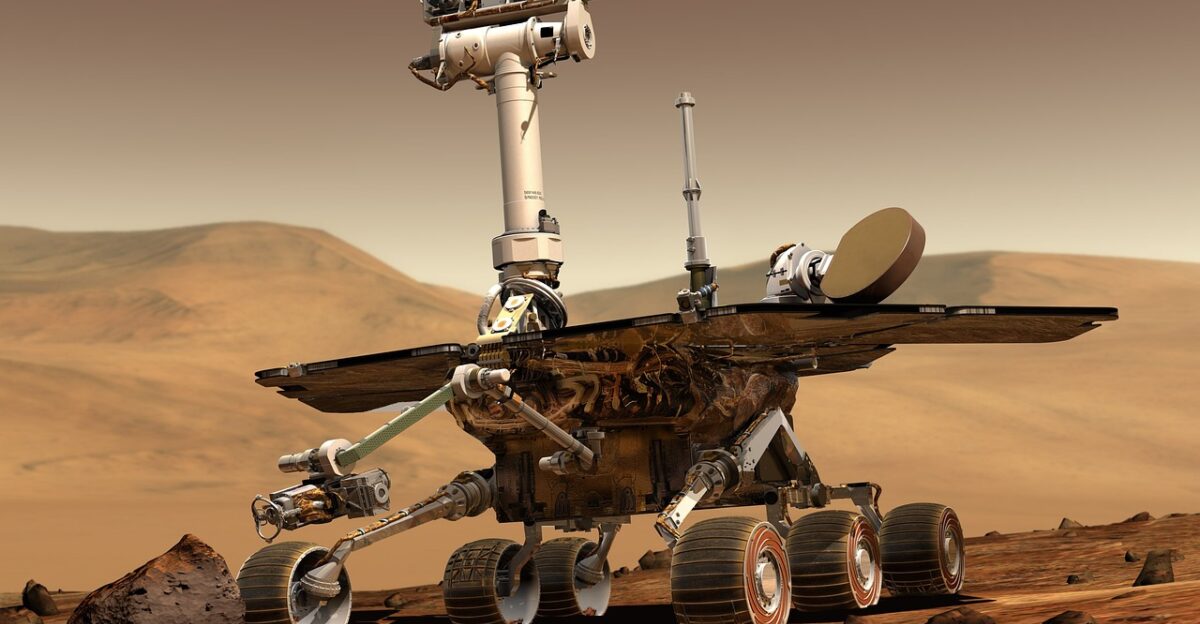

Implications for Technology, Safety, and Exploration

The discovery of remote touch has immediate and far-reaching applications. In robotics, the tactile sensor market is projected to grow from $500 million in 2025 to nearly $1.8 billion by 2033. Current sensors require direct contact, limiting their effectiveness in visually obscured or hazardous environments. Remote touch introduces a new class of non-contact tactile sensing, enabling robots to detect buried or hidden objects before impact. This capability could revolutionize search-and-rescue operations, where robots navigating collapsed structures might avoid destabilizing debris and increase survival odds for trapped individuals. In planetary exploration, Martian rovers equipped with remote touch could sense obstacles beneath the surface, preventing accidents like the immobilization of the Spirit rover in 2009. Archaeology stands to benefit as well, with tactile sensors potentially reducing damage to fragile artifacts during excavation.

A New Chapter for Science and Education

The identification of remote touch as a distinct human sense challenges the traditional five-sense model still taught to millions of students worldwide. Updating educational materials to reflect this discovery will require coordinated, multi-year efforts across global curricula. Beyond the classroom, the finding prompts new questions about the evolutionary origins of this ability and whether other hidden senses remain undiscovered. Some researchers speculate that remote touch may have evolved incidentally, as a byproduct of the high sensitivity of human mechanoreceptors, rather than as an adaptation for a specific ancestral behavior.

Looking ahead, the recognition of remote touch not only expands our understanding of human perception but also signals a paradigm shift in how we interact with technology and the environment. As research continues, this breakthrough promises to reshape fields from robotics and medicine to philosophy and education, underscoring the dynamic and still-unfolding nature of human sensory experience.